The Brain and Memory

Episode #2 of the course How to improve your memory by David Urbansky

In today’s episode, I will provide you with basic information about your brain and memory.

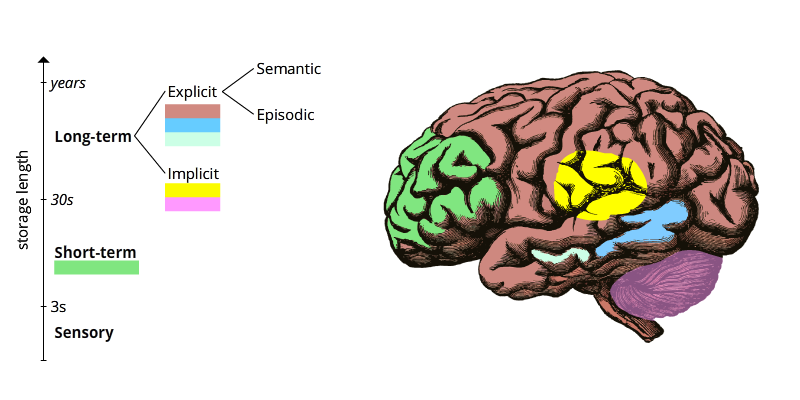

When we talk about “memory,” we mean the ability to store and recall information from our brain. There are multiple types of memory, as the following graphic shows:

Sensory memory: Sensory memory stores input from your senses, like sight, smell, or sound, for a very short time after the stimulus has disappeared. Since there is so much information coming in through your senses all the time (ever tried shutting your ears?), your brain discards this information quickly, retaining it for three seconds at most.

Short-term memory: According to Miller’s law [1], short-term memory holds seven, plus or minus two, pieces of information for up to 30 seconds. If your attention wanders, this information will be lost.

Long-term memory: There are no known limits to how much and how long information can be stored in long-term memory. This is where you must store information that you would like to keep and actively recall.

• Explicit long-term memory refers to storing information that you consciously experienced or learned. This type of memory can be further classified as “episodic” (things that have a time and place, such as when and where you ate your last muffin) and “semantic” (facts and general knowledge, such as the capital of Japan).

• Implicit memory is concerned with unconscious learning. The motor skills you develop when you learn to ride a bike or play table tennis are an example of implicit memory. When you ride a bike, you don’t have to consciously recall how to do it, you just ride along with your implicit memory.

All the techniques you will learn in this course help store information in your explicit long-term memory.

How Does Remembering Work, Anyway?

The memory process consists of three stages: acquisition, consolidation, and recall.

Acquisition is the introduction of new information to the brain. Consolidation is the process in which this information becomes stable and connected in long-term memory. Recall is the ability to access this stored information.

Where Is Information Stored?

The brain is an amazing organ, and thanks to neuroplasticity, it can reorganize and form new neural pathways throughout your entire life. Memories are not stored in one specific area, but rather are distributed across the brain, where they are stored as groups of neurons that fire together in the same pattern created by the original experience. A single memory must often be reconstructed by firing many neurons from different areas of the brain.

Short-term memories are processed in the prefrontal cortex, which is also responsible for other complex cognitive functions, such as decision making.

Explicit long-term memories are stored in the hippocampus, neocortex, and amygdala. The hippocampus stores episodic memories, the neocortex stores semantic memories, and the amygdala connects memories to emotions. Memories connected to strong emotions like love and fear are harder to forget, as they are strengthened by the neural connections to the amygdala. This is why post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is so serious and difficult to treat.

Implicit long-term memories are stored in the basal ganglia and the cerebellum. The basal ganglia is especially involved with movement and sequences of motor activity (e.g., learning to ride a bike). The cerebellum stores memory of fine motor skills, such as holding a pencil or typing on a keyboard.

This episode was a crash course on what memory is and where it is stored. Tomorrow, we’ll start with the first basic techniques for memorizing or, to use the jargon from this episode, for filling our explicit, semantic long-term memory with information. Get your mind ready!

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Recommended book

The Brain: The Story of You by David Eagleman

Reference

Share with friends