Thinking Fast and Slow

Episode #2 of the course Learning how to think clearly by David Urbansky

Welcome back! Today, you will learn why fast is not always good when it comes to thinking and how consciously slowing your thought process can make you smarter.

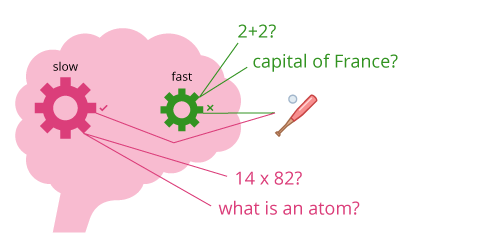

Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman classifies thinking into two separate systems [1]. System 1 is intuition, and System 2 is what we actually defined as thinking earlier. Let me explain.

System 1 is an automatic system. It is intuitive, effortless, and involuntary. For example, if somebody were to ask you to compute 2+2, you would not need any effort to come up with the right answer. In fact, you probably could not avoid thinking of the answer even if you wanted to. You involuntarily solve the problem without thinking about it. Same goes if you were asked to name the capital of France (unless you failed geography).

System 2, on the other hand, is voluntary and requires a great deal of energy and effort. For example, unless you are a math genius, your System 2 will be engaged when trying to compute 14×82. Unlike 2+2, the answer here does not come effortlessly. You have to remember the algorithm and compute the answer step by step.

Everything you do regularly becomes effortless at some point, and that is usually a good thing. When it comes to thinking, your brain also wants to be efficient and expend as little energy as possible. Your brain will therefore try to answer problems involuntarily with the energy-preserving system 1 first.

The process of learning a new language is a great showcase for how thinking patterns move from the exhausting System 2 to the effortless System 1. In the beginning, you are slow when constructing a sentence, thinking about articles, tenses, and declinations. The more you practice, the less you think about these issues, and at some point, speaking the new language becomes effortless. Have you ever struggled to explain a grammar rule from your mother tongue to a non-native speaker? This is because you suddenly have to ask your System 2 for help to find the underlying rules that you now follow unconsciously and automatically with your System 1.

The game of chess is another great example of the transition of thought from System 2 to System 1. Beginners will spend a long time thinking (System 2) about which move to make and what the possible consequences are. Masters at the game, however, read the positions of pieces on the board similar to a sentence in a foreign language that they understand. They don’t have to think so much consciously, but rather let their automatic, intuitive System 1 handle it.

Quiz Time

Let’s put your System 1 and System 2 to the test in what some call the world’s shortest intelligence test [2]. Ready to answer three short questions? Write down the answer for each one and then keep reading.

1. A bat and a ball together cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

2. If it takes 5 machines five minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

3. There is a patch of lily pads in a lake. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half the lake?

These questions look simple and fool your brain into using System 1 to quickly give you an automatic answer. Common results are that the ball costs $1, it takes the machines 100 minutes, and it takes 24 days to cover the whole lake. However, if you slow down and use System 2 to think about these questions, you will realize that the ball costs $0.05, it takes the machines also just five minutes, and the lake would be half covered on day 47.

If you did not get all three right, you are in good company. Only 17% of the students in the study [2], who were from Ivy League schools such as Yale and Harvard, got all three correct.

How to Use This Knowledge

Now that you have learned about these two systems, you understand that you can consciously move tasks from System 1 to System 2. When solving a problem, you can actively slow down, discard the first answer that comes to mind, and use other thinking tools (covered in later lessons) to come up with better or more creative answers.

See you in tomorrow’s episode, where you will learn about involuntary influences on your thoughts and how to detect them.

Recommended video

Recommended book

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

References

[1] Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

[2] Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making by Shane Frederick

Share with friends