The Middle Ages—Philosophies of Life and Love

Episode #3 of the course Women in philosophy by Will Buckingham

The “Middle Ages” is the long period of roughly 1,000 years between the fall of the Roman empire and the rise of the Ottoman empire, more or less between 500 and 1500 CE. During the Middle Ages, the pagan religions of Greece, Rome, and pre-Christian Europe were in retreat, and Christianity reigned supreme. Women continued to be excluded from public life and debate, but the existence of religious institutions sometimes allowed women to gain an education and gave them a platform that enabled them to engage in philosophical debates.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179 CE)

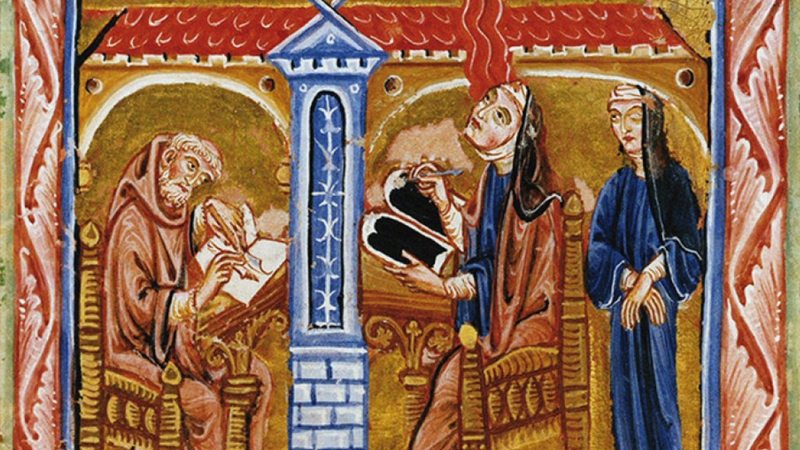

Hildegard of Bingen was a philosopher, writer, mystic, and composer whose works are still listened to today. She was born in Germany, the daughter of a noble family, and entered a convent at the age of eight. Hildegard became extremely well-read and was fluent in Latin. At the age of 18, she became a nun. Two decades later, she was appointed Mother Superior with responsibility for her own nunnery.

Hildegard’s philosophy had its origins in the ecstatic visions she had from an early age. The direct nature of these visions puts her own work slightly outside of the traditions of philosophical debate (she writes at one point, “I understood the writings of the prophets, the Gospels, and the other saints, and of certain philosophers, without any human instruction”). However, her accounts and interpretations of these visions are philosophically interesting.

One of Hildegard’s key ideas is the “fiery life” (ignea vis) that animates existence and the “greenness” (viriditas) that sustains it—the flourishing, budding, growing abundance of life. Hildegard writes that, “For air lives in greenness and flowers, waters flow as if alive, the sun, too, lives in his light, and when the moon comes to her decline she is kindled by his light, as it were to live again…”

There has been a renewed interest in Hildegard from contemporary philosophers working at the meeting point of environmental philosophy and feminism.

Héloïse and Her Philosophy of Love (1101-1164)

The story of Héloïse and her lover, Abélard (1079-1142), is one of the most famous in all of the Middle Ages. Héloïse was already well on the way to becoming a famous scholar when she went to study with one of the most renowned philosophers in Paris, Pierre Abélard. The two began an affair. When Héloïse became pregnant, Abélard sent her to stay with his sister. Héloïse gave birth to a boy called Astrolabe. Against Héloïse’s wishes, in an attempt to salvage Abélard’s career, they married in secret. The scandal caused by the affair led eventually to Héloïse’s exile in a nunnery and Abélard’s castration at the hands of an angry mob. Abélard had no other choice than to become a monk.

Héloïse is often considered an early feminist, in particular for her criticisms of marriage. In her letters to Abélard, she writes that she “preferred love to wedlock, freedom to a bond,” contrasting the unfree, contractual nature of marriage with the freedom of non-contractual love. She goes so far as to equate marriage with a form of prostitution.

But Is It Philosophy?

Here, we might ask, “But is it philosophy?” Would we be better off seeing Hildegard’s mysticism as a part of theology or Héloïse’s criticisms of marriage as social critique? But similar arguments made by men often are considered as philosophy. To take two recent examples, Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) wrote a book called Marriage and Morals, which critiques marriage, and French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) wrote about élan vital, or “vital impetus,” an idea not dissimilar to ignea vis. This may say a lot about the gendered way we read men and women philosophers.

Tomorrow, we are going to move on to the 18th century to explore a woman who directly challenged the primacy of male voices in society and the exclusion of women. This woman was Mary Wollstonecraft.

Further learning

Reading: For more on Héloïse, read her letters to Abélard

Podcast: “Leading Light: Hildegard of Bingen” by History of Philosophy

Share with friends