The Battle of Britain

Episode #4 of the course Ten turning points of World War II by Patrick Allitt

About the Battle of Britain, Churchill declared in Parliament, “Never, in the field of human conflict, was so much owed, by so many, to so few.” The “few” were the British fighter pilots who, day after day in the late summer of 1940, fought aerial dogfights against German bombers and their fighter escorts over the southeast of England and London. Denying Germany command of the air, they scotched Hitler’s plans for “Operation Sea Lion,” a seaborne invasion.

Hitler, having conquered Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France in quick succession, had begun to feel invincible. Allied with Italy to the south and on good terms with Francisco Franco’s Spanish dictatorship to the west and Stalin’s Soviet dictatorship to the east, he faced only one remaining enemy: Britain. Its soldiers had come home from Dunkirk but had left behind nearly all their equipment and had not demonstrated that they could put up much of a fight.

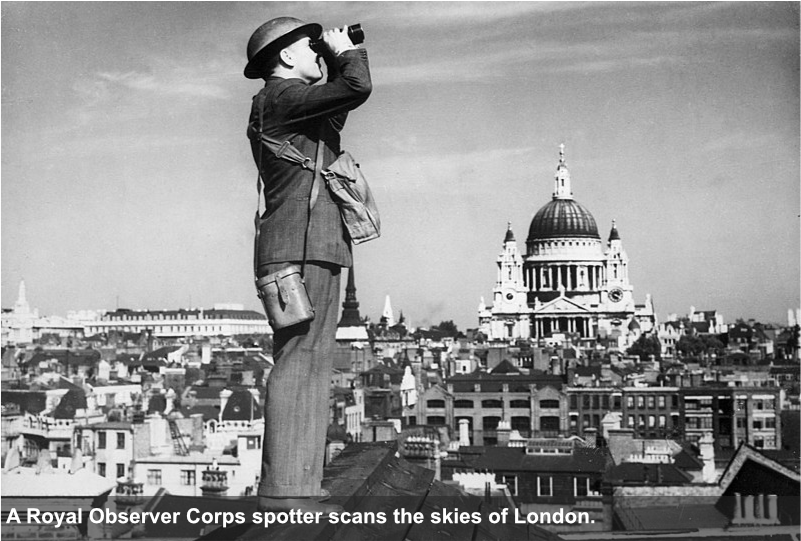

During the 1930s, however, as the Nazi danger had come into sharp focus, Britain had improved its air defenses. It now possessed a line of radar stations along the coast, which could detect approaching air raiders. They were linked to a command center that could “scramble” interceptors, so they would already be at high altitude when the raiders appeared. Britain also possessed high-quality fighter aircraft, Hurricanes and Spitfires, that could fight head to head with the best German fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. They were more than a match for Germany’s slow-moving and vulnerable bombers.

German raids began in early July 1940, at first concentrating on ships in the English Channel but soon moving to attack British airfields and radar stations. Destruction of the radar would have crippled Britain’s rapid communication system, but the German commander, Hermann Göring, failed to recognize their centrality, and shifted to other targets. His pilots were more experienced than their adversaries. Some had fought over Spain during its civil war, aiding Franco’s rebellion against the Spanish Republic. Many more had flown missions over Poland, Holland, and France.

On the other hand, the German fighters had limited range. Escorting bombers to England, they could fight for only a few minutes before warning lights in their cockpits told them to turn back or risk running out of fuel. Those whose planes were shot down baled out into captivity, whereas RAF (Royal Air Force) pilots often parachuted to safety, to fly again in the ensuing days.

Both sides suffered high losses and found it difficult to maintain full strength. By then, Britain was producing 300 fighter planes every week. Its acute problem was finding sufficient pilots to fly them. Training in the use of such complex, high-powered machines could not be done overnight, and the RAF learned from hard experience that under-trained men were likely to be shot down almost at once. Luckily, it had on hand more than 500 Polish and French aviators, experienced fliers who had escaped to Britain and who proved vitally useful.

In September 1940, the Germans switched to night raids over British industrial and port cities. This phase of the battle is remembered in British history as “the Blitz.” The change reflected Göring’s realization that daylight raids were just too costly and that his bid to achieve command of the skies had failed. For the next nine months, British cities endured destructive raids, but they were insufficient to break civilian morale or reduce industrial production. On the contrary, they increased British determination to carry on the fight.

For the first time, Hitler had been checked in his ambitions. The Battle of Britain was his first taste of defeat. Churchill called the battle Britain’s finest hour, but he still had plenty to worry about and no way as of yet to reverse the German tide of conquest. Tomorrow, we’ll see how Hitler, thwarted in the west, made his single greatest blunder of the war: the decision to invade the Soviet Union.

Recommended book

The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality by Richard Overy

Share with friends