Systemic Constellations

Episode #9 of the course 10 tools for change by Kate Sutherland

You’re close to gaining all ten tools. This puts you in the small minority of folks who are true group geeks. I’m delighted!

You will be, too, with the Systemic Constellations framework in your toolbox. You’ll be able to sniff out hidden dynamics in groups that are invisibly shaping what you and others do.

What Are Systemic Constellations?

On a clear night, we can see recognizable patterns—constellations!—like the Big Dipper or Southern Cross due to the distances and angles between different stars.

Systemic Constellations are similar in that they allow us to see how a person or group understands the distances and angles between different elements of a human system. Who can see whom? Who “has my back,” or who is far away?

Through simple physical forms, Systemic Constellations are used the world over in hundreds of applications: from healing intergenerational trauma to helping corporations with mergers.

Origins

The pioneer of Systemic Constellations is Bert Hellinger, a German psychoanalyst. Many influences shaped his practice, including Virginia Satir’s work on family systems, Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy’s descriptions of hidden bonds and loyalties in families, phenomenology, and Hellinger’s 16 years as a missionary with the Zulus in South Africa.

The first systemic constellations emerged in the 1970s in the group aspect of Hellinger’s practice. Through close observation of how clients positioned people representing (standing in for) different family members, Hellinger discovered what he called the “orders of love,” three key patterns that in combination, can account for the myriad ways that human systems are functional or dysfunctional.

Bring your family or team into alignment with these key patterns, and you’ll help shift intractable dynamics toward greater health and vitality.

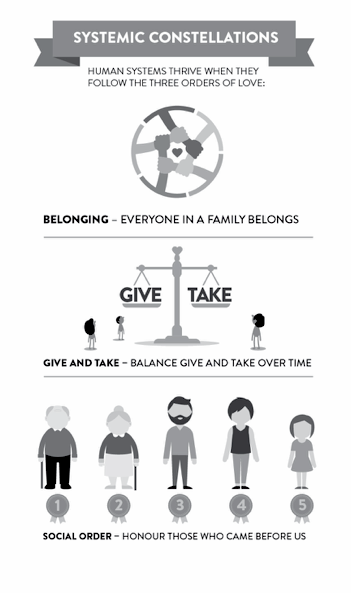

The Orders

So, what are these orders?

1. Belonging: As social creatures, humans have a primordial (survival!) need to belong, and belonging is the primary driver of our behavior.

2. Give and Take: Relationships, groups, and social systems are healthier where there is a balance of giving and receiving.

3. Social Order: It supports harmony in a human system when everyone knows their place in the social order.

You might rankle at one or more of these patterns. If you’re like me, for example, just the notion of social order used to get my back up.

With experience, I’ve come to respect the wisdom of this trio, and I hope you’ll try them for yourself.

Belonging

Our first and most important group is our family of origin. As a small dependent child, each of us did whatever it took to belong to our family, most of us being exquisitely wired to read faces and gestures, etc.

We learn from our families what it takes to belong in that context. This learning is typically implicit: We have a gut feeling that guides us rather than a conscious thought or decision. Then we unconsciously carry forward these body-based “maxims” into other contexts in the rest of our life, where these same maxims often get in our way.

We also seek to belong in any context that we deem important to us. This might be a congregation, a gang, a work team, or an out-group like “misfits”.

Give and Take

Our need to belong has a corollary in our need to serve the interests of the groups we belong to. Our felt sense (conscience) lets us know when we are out of balance with giving and receiving, like that feeling that it’s your turn to buy a round of beers at the pub (or that you’ve been buying too many rounds!).

Social Order

Social systems also thrive when social order is respected. This general pattern plays out many ways, depending on the context, based on two main ingredients: Those who come first go first (rank higher), as do those who contribute more to meeting the survival needs of the group.

These two ingredients are in tension in many systems: Coming first (higher seniority) is often the basis of social order in large institutions. This can lead to challenges when someone new is contributing more or when a new boss, parachuted in from outside, doesn’t honor and acknowledge those who have come before.

So What?

Think of a flock of starlings swooping and twisting “as one.” A scientist discovered that just three rules explain how thousands of birds fly complex patterns without collisions.

For human systems, Hellinger’s orders of love are like those flocking rules. If there are “collisions” in your team or organization, ask if your context is out of harmony with the orders of love. Something as simple as acknowledging your organization’s founder can be enough to unlock goodwill and creativity.

Tomorrow, you’ll gain the last tool, Integral Theory! It has profoundly shaped my work. I bet it’ll be the same for you!

Till soon!

Kate

Recommended book

Family Constellations Revealed by Indra Torsten Preiss

Share with friends