Remaking Philosophy—Women Philosophers and the Future of Philosophy

Episode #10 of the course Women in philosophy by Will Buckingham

Welcome to the final day of this course! I hope you have found it stimulating. We have covered a great deal of territory: from Diotima the priestess philosopher of love to Héloïse’s criticisms of marriage and defenses of desire, from the visions and “greenness” of Hildegard of Bingen to the plant-like vulnerability and flourishing of Martha Nussbaum, and from the political action of Hannah Arendt to the troublemaking of Judith Butler and to questions of intersectionality and race.

Accomplishments

My aim in this course has been twofold. The first is to raise some important questions about the tradition of philosophy in the West and to explore what might be called philosophy’s gender problem. As we have seen, it may be that this problem is not just when philosophy talks about gender but when it talks about other things as well. And it is a problem institutionally: Women are still vastly underrepresented with it comes to the statistics for the number of PhDs awarded in philosophy, the number of tenured philosophy faculty in universities, and so on. But my second aim has been to try and introduce you to some of history’s most intriguing and exciting women thinkers. And I hope that this course may also have encouraged you to go and read their work yourself.

Work in Progress

Over the last 100 years, in many parts of the world, there has been a huge social revolution in terms of women’s roles in society. When it comes to philosophy, this has meant a significant increase in the number of women involved more formally in philosophical debate and discussion. But there is still a lot more to be done. Traditional philosophy’s biases are deep-rooted. It is not easy to undo more than 2,000 years of intellectual history.

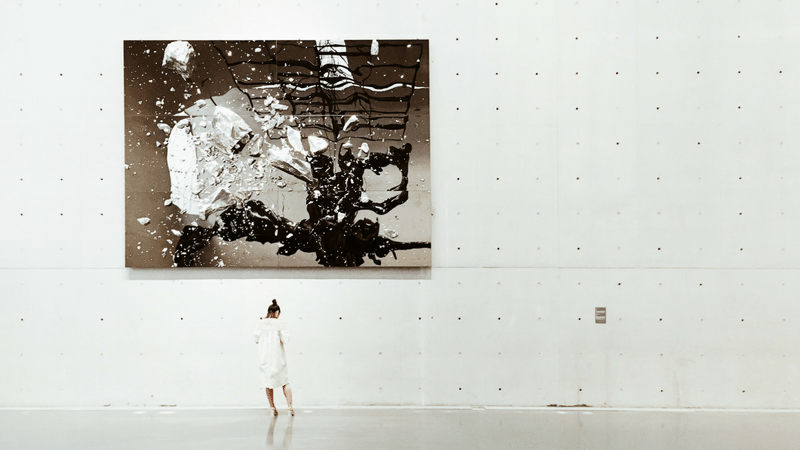

One day, perhaps, I will sit down in front of my computer, type the word “philosopher” into a search engine, and the images that come back will reflect more closely the gender balance of the human race as a whole (and, bearing in mind yesterday’s reflections on intersectionality, not just the gender balance). But until that day, this is still work in progress, and there is more to be done.

The Future of Philosophy

So, what about the future? There are no guarantees here, but I want to end this course with a couple of ideas about why, if philosophy could overcome its gender problem, it might be good for everyone.

Firstly, if philosophy truly aims to ask the deepest questions about human experience and if it does not take into account the experience of all human beings, it is going to fail to live up to this challenge. Philosophy has been impoverished by its exclusion of women’s perspectives and voices. And until it can address this exclusion, it will never be able to reach its potential. It will—to take a term from Martha Nussbaum (and Aristotle)—never flourish as well as it might.

And secondly, the philosophical tradition is not just something dead, but something alive, something that shapes the way we think. If we want to address the inequalities that still pervade our societies, we have to address also the philosophical ideas that make these inequalities possible. Ideas about the natural inferiority of women, repeated endlessly by male philosophers, need to be dismantled, taken apart, and shown to be the nonsense that they are.

I hope that this course has made you think twice about the history of philosophy and about some of the deep-rooted problems within that history. But of course, philosophers should never be afraid of problems because it is only by taking them seriously that philosophy might be remade so it can speak more fully about life’s biggest questions.

Further learning

Reading: “Does philosophy have a problem with women?”—a short debate between contemporary philosophers Julian Baggini and Mary Warnock.

Resource: Diversity Reading List—for resources on philosophy in relation to woman and other underrepresented groups.

Share with friends