Pearl Harbor

Episode #6 of the course Ten turning points of World War II by Patrick Allitt

As mentioned yesterday, Germany made its greatest mistake in June 1941 when it invaded Russia. Japan made its greatest mistake in December of the same year when it attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. In both cases, the initial shock for the victim was followed by a steady buildup of men and munitions, along with the determination to prevail at all costs.

Japan had begun a crash course of industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Emulating the Western imperial powers, particularly Britain, it had built a colonial empire in East Asia and a powerful navy. Its leaders, convinced that their nation needed more space and more direct access to raw materials, gambled that a shattering blow against the US Navy would lead the Americans to negotiate peace and leave the Pacific uncontested.

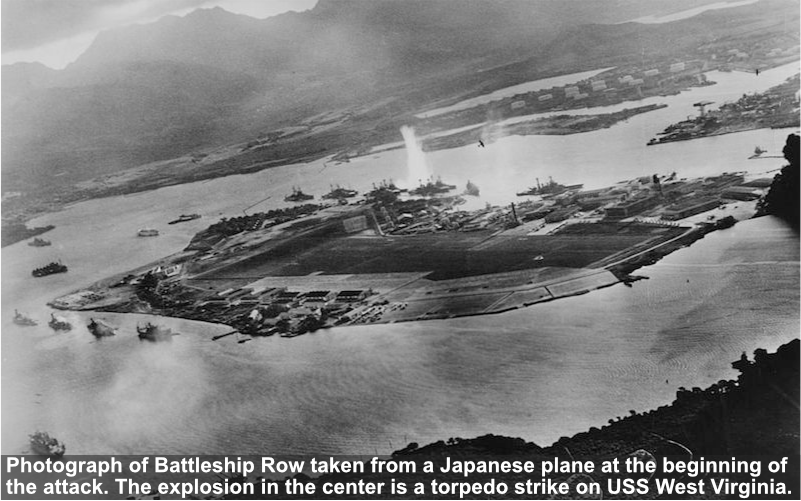

In great secrecy and preserving radio silence, the Japanese aircraft carrier fleet left its base on November 26 and sailed by an indirect route to its attack position 200 miles north of Hawaii. On a Sunday morning, when they calculated the Americans would be least expecting it, they launched 360 heavily armed aircraft, mostly torpedo bombers. American radar observers saw dozens of blips on their screens but assumed they were witnessing an equipment malfunction or a few friendly aircraft, rather than an actual mass attack.

Many of the American sailors were asleep, on shore leave, or otherwise unprepared for the attack. Few American interceptor planes left the ground—188 of them were destroyed where they sat. Among the battleships sunk that morning were the Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and California, along with many others severely damaged and a death toll of over 2,300. By happenstance, the Americans’ aircraft carriers, which were going to prove decisive in the Pacific battles that followed, were at sea on exercises and escaped destruction.

Pilots returning to the Japanese carriers reported the success of their surprise attack and hoped they could refuel, rearm, and return to finish the destruction, especially by attacking the complex of dockyards and fuel tanks. Admiral Nagumo, however, refused, fearing high losses at the hands of an enemy that would now be alert and enraged and knowing that Japanese attacks elsewhere would need his fleet’s support. This failure to follow up on their initial success was a lost opportunity.

The whole Japanese gamble was, in the long run, disastrous. American rage and indignation at being attacked without provocation and without a declaration of war made certain that it would never negotiate peace terms. Instead, it would fight until Japan surrendered unconditionally. In a speech to Congress, President Roosevelt declared December 7, “a date which will live in infamy” and prepared to mobilize the full force of the American economy.

Winston Churchill, learning of the attack later that day, understood its magnitude and, ironically, its benefits. He had been trying unsuccessfully for a year and a half to draw the United States into the war against Germany. Roosevelt, unwilling to annoy the powerful isolationist lobby, had resisted, offering Britain military and commercial aid and a generous “lend-lease” program but no troops. Now, at a stroke, the political situation was transformed. America would go to war.

But would it go to war against Germany? Hitler, in a blunder almost as grave as his invasion of Russia, declared war against the United States on December 11. Had he not done so, the United States might have directed its forces against Japan alone, bringing no benefit to beleaguered Britain. Now, by contrast, Roosevelt could meet with Churchill (who spent that Christmas at the White House) to plan campaigns against both Germany and Japan.

Tomorrow, we will see how the British and American allies had to solve the problem of transporting men, equipment, supplies, and food across the Atlantic Ocean in the face of an aggressive German submarine campaign. The Battle of the Atlantic was vital, but unlike most of the other turning points in this series, it lasted for years.

Recommended book

Pearl Harbor: From Infamy to Greatness by Craig Nelson

Share with friends