Mental Models

Episode #5 of the course Learning how to think clearly by David Urbansky

Today, you will learn how you can use mental models in your thought processes to grasp bigger ideas and form connections faster. The quality of your thinking increases with every mental model you learn. Sounds good, but what exactly is a mental model?

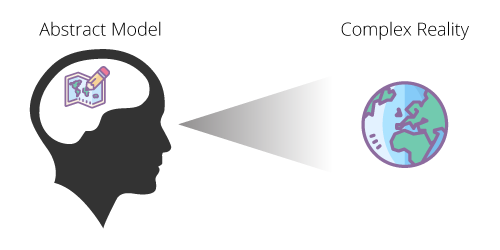

A mental model is a simplified observation of a certain part of reality that you can keep in your head.

Let me explain further with examples. Without you noticing, I already taught you one mental model in the lesson about cognitive biases. As you’ll recall, this mental model is the observation that people make systematic thinking errors and you need to be aware of them. There are thousands of mental models out there (here is a good list of over 100). I have selected a few important ones that can help you with clearer thinking:

Occam’s Razor states that if there are multiple explanations, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected. Suppose that you can’t find your keys and think that you either left them somewhere and just can’t remember (the only assumption is that you are forgetful) or you think aliens stole them (the assumptions here are that aliens exist, they visit Earth, they’re interested in your keys, and they are thieves). Which explanation should you accept?

The Pareto Principle (or 80/20 Rule) asserts that for many events, 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. So, when you want to achieve a certain goal, try to find the steps that have the biggest impact. For example, if you want to improve your thinking (see what I did there?), you should learn the most useful mental models, and you will get a majority of the benefits! Billionaire investor and wise man Charlie Munger said, “80 or 90 important models will carry about 90% of the freight in making you a worldly‑wise person.”

First Principle thinking refers to breaking a problem into its core parts. If you understand the parts, you can creatively re-assemble them and come up with creative new ideas. For instance, let’s say that you just ate an awesome lasagna with a crispy cheese top and a juicy middle. You would like to create something like that too. Now, you could try to get the exact recipe and recreate it (but then you can only recreate this one dish), or you could apply first principle thinking and understand the core parts, i.e., the ingredients, temperature, cooking time, preparation steps, etc. If you do this, you’ll be able to create other dishes with other ingredients, since you now understand the core ideas of cooking.

Thought experiments are a great way to simulate a possible reality in your head. Einstein’s breakthrough with special relativity goes back to a thought experiment he performed as a teenager [2]. But you don’t have to be a scientist to get value out of this mental model. Just ask yourself “what ifs” for any task you have. Imagine that you are planning a wedding. You do not want any hiccups on the big day, so preparing for every eventuality is key. What if it rains? What if red wine gets spilled on the wedding dress? What if the ring bearer is abducted by aliens? Thought experiments are fast, free, and might lead to surprising new insights. A Nobel Prize in Physics can’t be ruled out!

Inversion states that you should tackle a problem backward instead of forward. Let’s say that your “problem” is that you want to get healthier. Forward thinking means you think of all the things that would get you there: eating more vegetables, getting enough sleep, working out a few times a week, and so on. This is all great but requires serious dedication. However, avoiding mistakes is often much easier than doing the right thing! So, if you invert your problem-solving approach and think of the things you should NOT do to get healthier, you may come up with a list like eating fast food, pulling all-nighters, taking the car everywhere, and snacking before bed. It is likely easier to not do a few of those things, and just like that, you are on your way to your goal of getting healthier.

If you want homework, put these mental models to use! Find the smallest changes that make the biggest impact, run thought experiments, and invert your thoughts on something you do regularly, and see where it gets you. Tomorrow, we’ll talk about how you can set up your brain gym to practice your thinking—don’t worry, no dumbbells required.

Recommended video

Recommended book

Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger by Charles T. Munger

References

[1] Mental Models by Farnam Street

[2] Chasing the Light: Einstein’s Most Famous Thought Experiment by John D. Norton

Share with friends