James Watt

Episode #9 of the course Inventors who changed the world

James Watt (1736-1819) was a Scottish engineer who developed the type of steam engine that was essential to the industrial revolution in mines, paddle-boats, and factories, for example. Watt had unique insights into thermodynamics, which enabled him to transform the earlier Newcomen steam engine into a much more useful device. Watt also created machines for copying both written materials and sculptures, among other inventions.

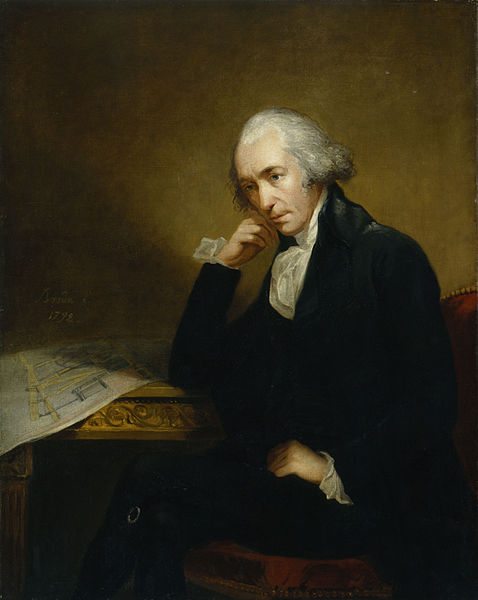

Carl Frederik von Breda. Portrait of James Watt, 1792

Carl Frederik von Breda. Portrait of James Watt, 1792

Watt was mostly home-schooled and displayed an early aptitude for mechanical engineering and mathematics. His father ran a ship-building business, among other enterprises, and young Watt first became familiar with metalwork and the forging of mechanical instruments in his father’s workshops.

At the age of eighteen, Watt went to London to study instrument-making for a year, then returned to Scotland, setting up a business in Glasgow, where he made and repaired brass instruments such as quadrants, rulers, scales, telescopes, and barometers. He was blocked by the Glasgow Guild of Hammermen because he hadn’t apprenticed for seven years, but then an unusual opportunity saved his career.

The University of Glasgow was gifted a set of astronomical instruments requiring expert care and Watt, being the only mathematical instrument maker in Scotland, was hired to restore them. After the instruments were installed, Watt maintained and repaired scientific instruments at the university until 1759, when he partnered with a businessman to produce a line of toys and musical instruments. That business lasted into the 20th century.

James Eckford Lauder. James Watt and the Steam Engine: the Dawn of the Nineteenth Century, 1855.

James Eckford Lauder. James Watt and the Steam Engine: the Dawn of the Nineteenth Century, 1855.

Then, in 1763, Watt was charged with repairing the university’s model Newcomen engine. Watt could barely make it work. He experimented to eventually realize that most of the thermal energy (heat) in the steam was being wasted re-heating the engine cylinder during every cycle after cooling it with cold water to condense the steam and lower the pressure. The engine wasted most of its energy rather than converting it into motion.

Eventually Watt came up with a breakthrough solution—to condense the steam in a separate chamber, away from the piston, and insulate the cylinder so it didn’t absorb energy. The resulting engines converted five times more of the available energy into work.

A steam engine built to James Watt’s patent. Freiberg, Germany.

A steam engine built to James Watt’s patent. Freiberg, Germany.

Development was stalled for eight years due to a lack of iron workers capable of making the precision machine parts. Finally, in 1775, Watt partnered with Matthew Boulton, who had access to the best iron workers in the world, and the problem was solved by a machinist who had developed the techniques while making cannons.

Boulton and Watt were successful and became busy installing pump-engines in Cornwall mines for several years. Then, Boulton foresaw a new market in grain and cotton mills and exhorted Watt to invent rotary motion for his engine, which he did in 1781, implementing the sun-and-planet gear that converts piston movement into the rotation of a gear.

In the following years, Watt patented other improvements, such as the steam pressure indicator, the throttle valve for regulating power, and the centrifugal governor to keep the engine from “running away.” Together, Watt’s innovations produced the practical and versatile steam engine that helped create the Industrial Revolution.

The inside of James Watt’s garrett workshop, preserved in the Science Museum, London.

The inside of James Watt’s garrett workshop, preserved in the Science Museum, London.

At the same time, Watt had other inspirations. Watt invented the first practical method for copying printed (or written) materials using sheets of paper moistened with solvents to transfer the ink from the original document. After much experimentation, he put together a complete device that was used in some offices into the 20th century. He later constructed machines for copying sculptures and medallions, which worked but were never patented.

Only a few years before his death, Watt traveled home on a paddle steamer—a product of his own invention. He died at home in 1819 at the age of 83.

In our next lesson, we consider Alexander Graham Bell, another Scotsman who changed the world!

Quote

“Raphael paints wisdom, Handel sings it, Phidias carves it, Shakespeare writes it, Wren builds it, Columbus sails it, Luther preaches it, Washington arms it, Watt mechanizes it.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Recommended book

1001 Inventions That Changed the World by Jack Challoner

Share with friends