Ivar the Boneless

Episode #4 of the course Vikings: History and mindset by Tom Shippey

Welcome to Lesson 4!

Today, we’ll talk about Ivar the Boneless, whose descendants dominated Irish politics for generations and who influenced English and Scottish history greatly.

Legend and History: Ragnar

According to his own saga, Ragnar Hairy-breeches’s wife was the daughter of Sigurd, killer of the dragon Fafnir and murdered by the Nibelung kings, themselves wiped out by the Huns in 437.

Ragnar’s son, Ivar, by contrast, is securely documented to the later 800s. The dates don’t fit at all. Ragnar’s link to legend is pure fiction. That does not mean there was no such person. Frankish chronicles mention a Viking called Reginherus, who attacked Paris in 845. He terrorized opposition by hanging 111 Frankish warriors in full view of their comrades, and the Frankish king paid him 7,000 pounds of silver to go away.

Twenty years later, the death of Ragnar became famous. His saga says he was killed by King Ella of Northumbria, who put him in a pit full of adders. The last words of his “Death-Song,” sung from the snake-pit, are, “Laughing shall I die.”

19th century artist’s impression of King’s Ella of Northumbria execution of Ragnar Lodbrok.

Ragnar was laughing—Viking humor again—because he knew the “little pigs,” his sons, would avenge the death of “the old boar,” their father. The death-song and the snake-pit must be fictional too, but there is no doubt about the coming of the “little pigs.” The most famous of them was Ivar.

The Career of Ivar

Ivar started his Viking career in Ireland, where he is recorded as active in 857-63. He then disappears from Irish record—but only because he had turned to England.

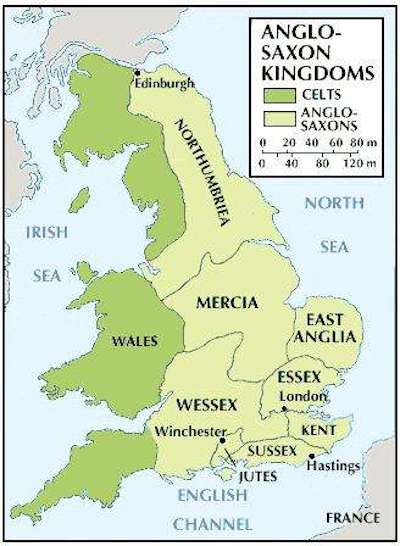

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the arrival of a “great army” of Vikings in 865. They landed in East Anglia, marched on Northumbria, and killed King Ella. Allegedly, they did so by means of the “blood-eagle,” a brutal form of execution that involved pulling the victim’s lungs out of his back and spreading them to look like an eagle’s wings.

As with all accounts of Viking atrocity, historians just don’t like to believe this, but the practice is mentioned several times in different poems and sagas.

The “great army” went back to East Anglia, where in 869, they killed King Edmund. His brother, Eadwold, made no attempt to take over but fled to become a hermit in Dorset far away.

Ivar then returned to Ireland, where he made a deal with another Viking leader called Olaf. The two of them in 870 captured Dumbarton Rock in Scotland, stronghold of the Strathclyde kingdom, taking a vast booty in slaves. After which, the “great army” turned on the English kingdom of Mercia, the English heartland. In 873, Burhred, king of Mercia, like Eadwold, gave up and fled to Rome.

The only resistance now left in England was King Alfred of Wessex, and the Vikings nearly caught him by a surprise attack in midwinter. Alfred got away, rallied his forces, won the Battle of Edington in 878, and made a treaty with the Vikings, effectively dividing England.

King Alfred of Wessex.

A Very Grisly Discovery

By the time King Alfred made a treaty with the Vikings, though, Ivar was dead. Archaeologists think they may have found his tomb, at Repton, the Mercian stronghold. He (if it was him) was laid in a stone sarcophagus, with more than 200 skeletons around him, many of them unusually big men, but showing few signs of battle wounds. An outbreak of disease among the Vikings, maybe?

Close by, though, was a man with a Thor’s-hammer pendant around his neck and terrible battle wounds, including a sword slash so deep, it must have emasculated him. Coins and radiocarbon dating are all consistent with a date in the 870s.

What Ivar’s career shows was that the Vikings were changing their goals. What they wanted now was not loot, but land. The easiest way to get that was to frighten off the kings of their target countries and take over as kings themselves.

Atrocity-executions, then, had a purpose. No one likes to admit it but Ivar’s strategy worked.

As for his nickname, the Boneless, the best explanation is that it really meant, “the Legless”—a compliment, calling him, in effect, a were-worm. Not quite “the mother of dragons,” like Daenerys, but as good as.

The Vikings, however, still had to reckon with King Alfred. We’ll cover this tomorrow.

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Recommended reading

Recommended book

Scandinavian Kings in the British Isles, 850-880 by Alfred Smyth

Share with friends