Early Chinese Civilization

Episode #8 of the course Human history and the first civilizations by Brian Fagan

Hello!

It’s time to travel farther afield, to examine pre-industrial civilizations in China. Most research has focused on northern China, where the earliest traces of increasingly complex kingdoms appeared before 2000 BC.

Origins

In about 4000 BC, regional farming societies, collectively known as the Lungshan, flourished in northern and southern China. They traded frequently with one another in copper and other materials.

In the Shanghai delta region of the south, wealthy leaders ruled the Liangzhu culture. A huge social chasm now separated rulers and nobles from commoners. Increasingly intensive trade and warfare led to the emergence of Chinese civilization in about 2000 BC.

Xia and Shang

Chinese civilization emerged in a volatile political environment of competitive kingdoms at a time of cold, dry conditions and ever fiercer competition between different local rulers.

Between 1900 and 1500 BC, the city of Erlitou, south of the Yellow River in northern China, became a centralized kingdom with a densely populated urban core. Expert artisans fashioned elaborate bronze ritual vessels under the strict control of Erlitou’s rulers. They expanded their kingdom to obtain control of vital raw materials like copper, tin, and fine pot-making clay. Erlitou’s population rose as the city became the founding kingdom behind Shang civilization.

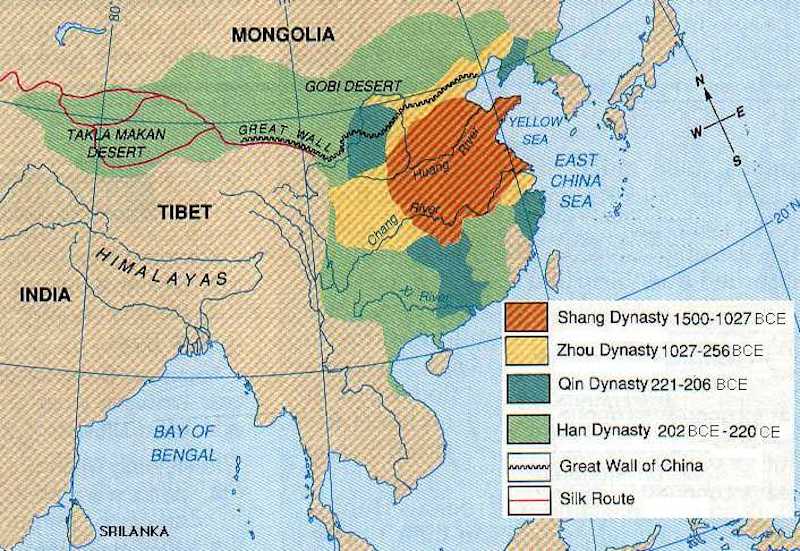

The map of Ancient China.

The founding dynasty of Chinese civilization is said to be the Xia, which emerged to prominence under the rule of Yu the Great, an expert soldier and flood control engineer. Xia was probably one dynasty of several headed by competing war lords, as Shang civilization emerged to longer-term prominence. It was most likely a loosely unified confederacy of competing small kingdoms. Despite constant warfare, the basic institutions of Shang civilization remained intact from about 1766 to 1122 BC. There were probably similar developments in the Yangtze Valley to the south, but they are still almost unknown. The larger area of Chinese civilization ultimately extended from northern China into the south, with a common, general cultural tradition that placed considerable emphasis on ancestor worship.

The Shang Dynasty

Shang rulers lived in about seven still virtually unknown capitals, near the middle reaches of the Yellow River. In 1557 BC, they moved their capital to Ao, which lies under the modern city of Zhengzhou, south of the Yellow River. About 150 years later, the capital moved to Anyang, closer to the river, where it remained for more than 250 years. The royal quarter was a network of compounds, palaces, and villages that covered some 310 sq. km (120 sq. miles) on the north bank of the Yellow River. The rulers and elite lived in mud and stick houses divided into large halls and smaller rooms. Two rows of temples with ceremonial gates stood in the middle. Numerous workshops for artisans lay at the edge of the royal precinct.

Eleven royal graves lie in a nearby royal cemetery dating to between 1500 and 1200 BC. Here, rulers lay in wooden chambers accompanied by slaves and sacrificial victims. Richly decorated chariot burials were excavated by brushing away sand from the cast of the wooden parts preserved in the soil.

Every early Chinese ruler stayed in power with the help of a strong army that was reinforced at short notice with thousands of conscripts. The leaders were constantly at war, expanding their territories or raiding for sacrificial victims in large numbers. Shang collapsed in 1122 BC at the hands of the neighboring Zhou dynasty, which extended its domains as far southwest as the modern city of Xi’an.

Emperor Shihuangdi and Unification of China

After centuries of constant warfare, a powerful warlord known as Zheng, “the tiger of Qin,” unified China’s states into a single kingdom in 221 BC. A ruthless conqueror, Shihuangdi is said to have forced 700,000 workers to labor on his burial mound and surrounding compound. He lies under an un-excavated burial mound that is said to be a map of China with the rivers and ocean outlined in mercury.

In death, he was protected by detachments of terracotta soldiers, which have been excavated on the eastern side of the mound. The fully armed figures have individual features. Two half-scale bronze chariots and their horses, as well as underground stables with horses that were buried alive, lie nearby.

In the next lesson, we’ll talk about Maya and Aztec civilizations.

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Recommended book

Early China: A Social and Cultural History by Li Feng

Share with friends