Directing Cognitive Effort

Episode #3 of the course The science of learning by Benjamin Keep

Welcome back.

So far, we have identified expert practices and created specific learning goals. One of the most overriding learning principles is the idea of cognitive load.

Cognitive Load

Cognitive load is the burden that a learning environment gives your attention. Solving a problem like 1 + 2 or 4 + 5 imposes low cognitive load. Proving Fermat’s last theorem: high cognitive load. If you’re a musician, playing the melody to “Silent Night” imposes low cognitive load. Playing in a symphony orchestra: high cognitive load.

When cognitive load becomes too high, people make more mistakes. They don’t remember what they’re seeing or hearing. The brain just has to work too hard to make sense of everything that we’re asking from it. Our attention is limited; as a result, learning suffers.

Learning experiences that impose the right amount of cognitive load are efficient. Too low, and your brain isn’t engaging in the way it could be. Cognitive load that’s too high means that you can’t keep what you’re learning straight. It’s not that you learn nothing under high cognitive load, but you would retain so little.

An ideal learning experience strikes the right balance—challenging but not overwhelming.

Good Load and Bad Load

Some load is necessary to learn: If you want to become good at geometry, solving geometry problems will impose a high but necessary load. Other load is unnecessary and costly. That funny story, those distracting graphics, the words that you don’t understand, the intermittent beeping from your phone … they all will eat away at your attention, making your learning less efficient.

Good load is load that directly relates to what you’re trying to learn. Bad load is load that does not.

For example, a course on programming that has you rewrite snippets of code asks you to spend your cognitive effort on transcription. You’re spending time copying text, but copying text is not the vital skill for becoming a good programmer. Students who take verbatim notes during a lecture do something similar. They may have taken thorough notes, but their brain was almost entirely focused on copying down what the teacher was saying, not on understanding the material.

Any time you find yourself doing an activity or paying attention to something not related to the skill you’re trying to acquire, your learning experience could be more efficient.

Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load

Learners often find themselves in situations with high cognitive load: The textbook is too dense; the lecture is poorly organized.

Teachers can reduce cognitive load in various ways. Organizing the lecture, simplifying diagrams, and using less jargon all improve learning. These things work, in part, because they reduce unnecessary load on the learner.

How Can These Ideas Help?

The first lesson of work on cognitive load is to remove all distractions. When you are learning, do not take phone calls, play videos, or check social media.

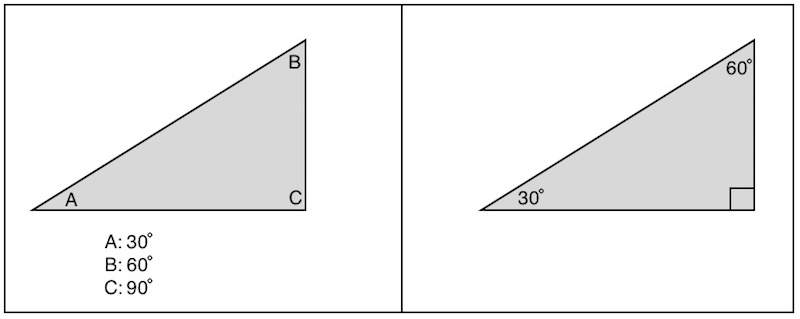

The second lesson is to learn to recognize aspects of the task that unnecessarily tax your brain. Even small things can impose load. Imagine the diagram below as part of a geometry problem. Which way of labeling the angles imposes less cognitive load?

The triangle on the right is better. The triangle on the left asks the problem solver to remember what the angle measurements are as they look at the triangle. The one on the right makes it easier to focus on the main point of the task, which is solving the problem. Make tasks easier on yourself by relieving unnecessary cognitive load.

The third lesson is to recognize when you are overloaded. Forget what you just read or just heard? Try to apply the techniques that good teachers use to reduce load. Can you re-organize the information in your own way? Or simplify a diagram so that it makes sense to you?

Take a moment to analyze your current studying approach through the lens of cognitive load. When working on my Chinese, words can come too fast for me to understand. I might try slowing the audio recording down so I can hear the words more clearly or writing down what’s being said so I can think about the organization of the sentence.

Next lesson, we’ll discuss strategies that help us remember things.

Happy learning!

Ben

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Recommended book

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change by Stephen R. Covey

Share with friends