Aphasia

Episode #5 of the course Introduction to clinical neuropsychology by Alicia Nortje

Welcome to Lesson 5. Aphasias are fascinating, and present us with many questions about language—for example, why are reading and writing separate? What types of language errors do patients make and what does this tell us about how language is represented in the brain? Can patients who struggle to produce language still produce thought with their inner-voice (and how would one test this)?

Ready to learn? Then let’s begin!

Definition of Aphasia

Aphasia is a condition where patients struggle to produce or understand language. The term, “aphasia” derives from Greek for: “a” means “without”, “phasis” means “speech” (which stems from “phanai” – “to speak”), and “ia” means “a condition”.

Because aphasia is a language disorder, this condition should not result from memory difficulties or apraxia (you’ll learn about this tomorrow). Aphasia affects language universally, across all mediums, therefore difficulties with producing language should be evident in verbal and written production. Patients who can’t understand language will show impaired comprehension for vocalized and written language.

Types of Difficulties Seen in Aphasia

When assessing aphasia, the following is important:

1. Does the patient have fluent or nonfluent aphasia? Fluent aphasia is when the patient can produce words and sentences at a normal/rapid rate, whereas nonfluent aphasia describes speech that is slow and halting.

2. What type of mistakes does the patient make when speaking? Do they use made-up words (i.e., neologisms)? Do they make semantic errors, using words that are connected in meaning (e.g., saying “hammer” instead of “saw”)? Do they make phonemic paraphasias, where they say words that sound similar to the intended word (e.g., “bat” instead of “mat”)?

3. Do patients have word-finding difficulties? Do they talk around the topic because they’re not able to find the words to describe what they’re talking about (i.e., circumlocution)?

4. Can the patient repeat single words or phrases? What types of errors do they make (e.g., semantic errors or neologisms)?

5. Does the patient display echolalia, where they meaninglessly repeat phrases and words that they heard spoken?

6. Comparatively, which is worse: production of language, comprehension of language, or repetition?

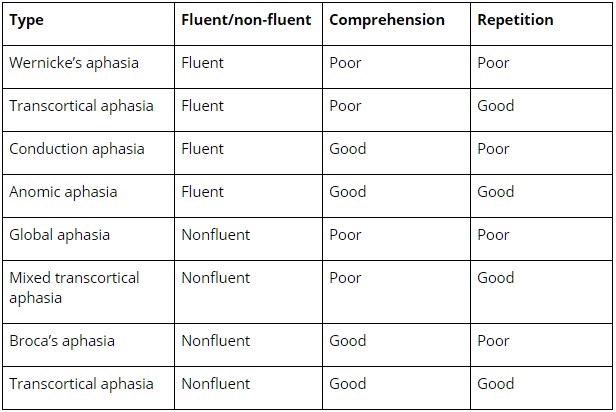

The table below helps consolidate this information and summarises the characteristics of eight types of aphasias.

Types of Aphasia

There are eight classical types of aphasias, but the two most well-known types are Broca’s aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia. Both types of aphasias play an important role in how we understand language.

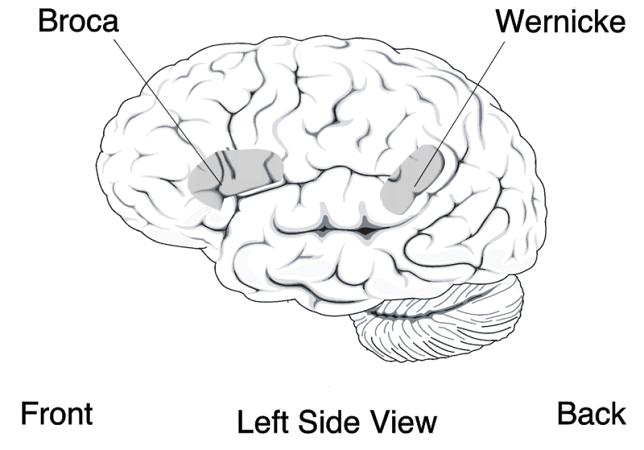

Wernicke’s aphasia is described as fluent aphasia: patients can produce speech at a “normal” rate and can produce well-formed sentences. Despite a normal speech rate, these patients make mistakes like neologisms, which are nonsense words, and some parts of speech are often missing (e.g., nouns and verbs). Their comprehension is often impaired: These patients cannot understand commands or questions, and they appear unaware of their comprehension errors. These patients really struggle to repeat words and often make semantic errors. This aphasia results from damage to Wernicke’s area, which is located in the left superior temporal gyrus, close to where the temporal and parietal lobes join.

Broca’s aphasia is non-fluent aphasia, meaning that these patients talk slowly and struggle to produce words. Their sentences are short and contain grammatical errors (e.g., lots of missing articles like “the”), and poor poorly at repetition. Their comprehension is comparatively better—they are able to understand commands and questions. Broca’s aphasia was first described by the neurologist Paul Broca who described a patient named Tan-Tan; Tan-Tan’s name is a result of the only words that he could say. After Tan-Tan died, Broca performed an autopsy and discovered that Tan-Tan had an injury in the left frontal lobe, next to the lateral sulcus. This brain area is known as Broca’s area.

Contribution to Our Understanding of Language

Together Broca’s aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia contributed to our understanding of language. Autopsies of patients with these types of aphasia suggest that language is localized in the left hemisphere for most people (90% of right-handers, and 70% of left-handers) and that aspects of language—such as comprehension and production—are not confined to the same area of the brain. Furthermore, spontaneous production of speech is different from repetition; it is hypothesized that impaired repetition (as in conduction aphasia) is a result of a broken connection between Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. Finally, there are interesting questions about how language is mapped in the brains of patients who speak sign language, and are multilingual, and whether aphasias manifest in the same way. There is some evidence that shows that individuals who speak sign-language and who have suffered an injury to Broca’s area demonstrate the same slow production of language, suggesting that the representation of “language” is broader than only a vocalized action.

Conclusion

Today we learned about aphasias. Aphasia is the most well documented neuropsychological condition and has contributed extensively to both psychology and linguistics.

Tomorrow we’ll learn about apraxia!

Cheers,

Alicia

Recommended videos

Example of fluent aphasia with some interesting paraphasias

Videos of Wernicke’s aphasia (1, 2)

Share with friends