White Wine Appearance

Episode #9 of the course Introduction to red and white wine by Paul Kalemkiarian

So, you know the process by which white wine is made. Now, let’s take a closer look at the subtle hues and indicators that can tell you something about the wine even before you smell or taste it.

People often take the color of white wine rather more for granted than they do for red. In their subtle variations, white wine colors can tell you a great deal about a wine. In a well-lit room, hold your glass up against a white background. What do you see?

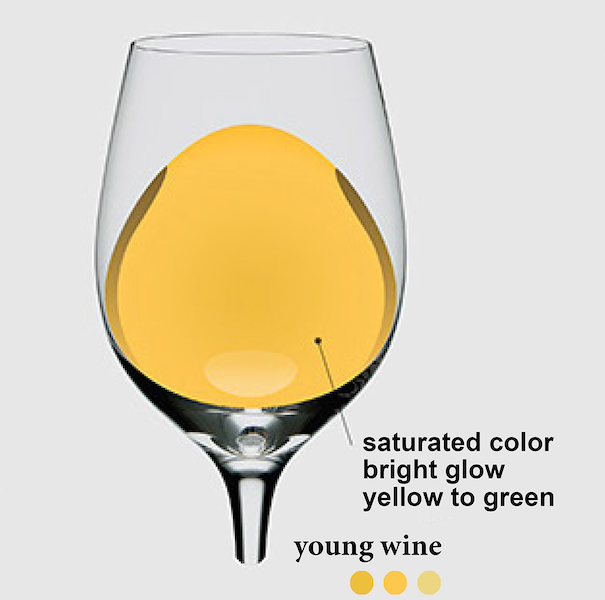

Young white wine from cool climates tends to be extremely pale, ranging from the near-colorless Loires and Moselles to the green-tinged Chablis. Warmer climates will generally give their wines a deeper color. A good look at the wine may help you guess whether it is a Burgundy or a California Chardonnay, assuming both are unoaked and of a similar age.

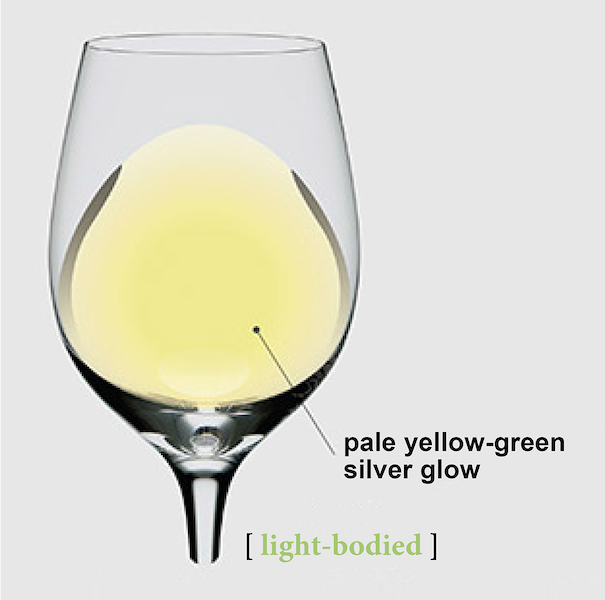

Very light, transparent white wines have had minimal contact with the grape skins when they were being made. These wines are typically crisp and refreshing. Pinot Grigio, Riesling, and Vinho Verde are among the lightest wines you’re likely to encounter.

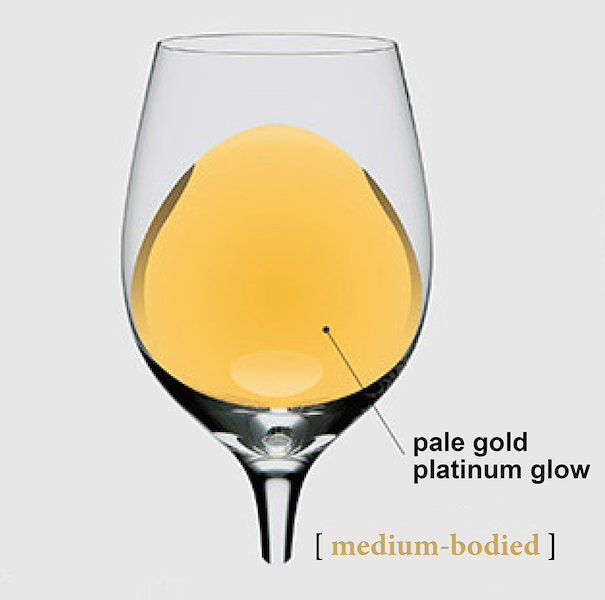

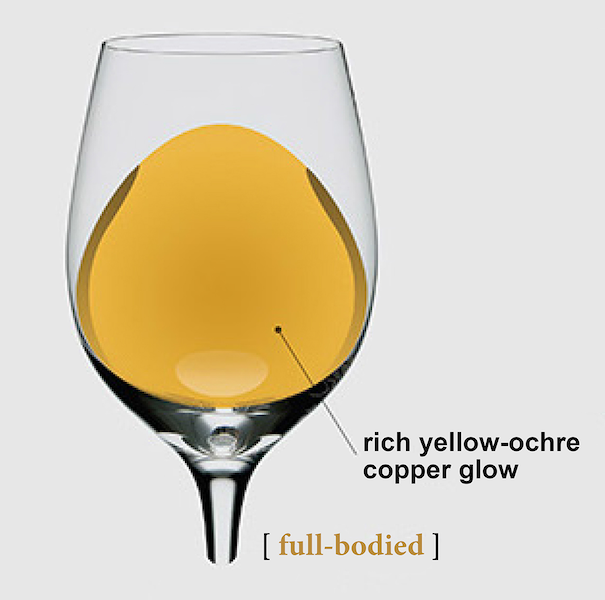

Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadet are a slightly deeper straw color. Unoaked Chardonnay, Viognier, and Chenin Blanc have a more golden hue. If the wine has been oaked, that golden color becomes even more apparent in the glass.

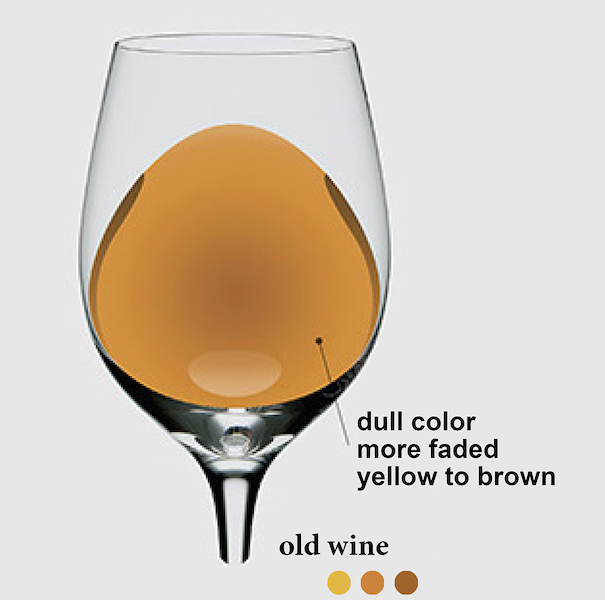

As they age, white wines grow increasingly close to a full, honey-gold color. Depending on the wine, this will indicate either that it has improved with maturity or warn you that it has “gone over the top” and become oxidized or “maderized.” Oxidation will take place when oxygen has been allowed to “get at” the wine, either in the barrel or in the bottle. Poor storage may be at fault and heat can be a particular problem. In fact, the term “maderization” refers to the way in which dark-colored, oxidized white wines come to resemble Madeira, a dessert wine that is actually heated in order to achieve just this effect.

A deep color may also indicate that the wine has been aged for some time in large oak barrels, where it has taken on the appearance of an older wine. Not all but many white wines from France, Spain, Portugal, and Italy employ this in their traditional winemaking.

While sweet white wines are often made to be kept, the vast majority of dry whites are best drunk young. With time, a Muscadet, for example, will lose its freshness, gaining nothing in return. At five years old, even a fine Alsace is beginning to show its age. Only those dry whites that combine sufficient weight with a reasonable sustaining acidity, such as fine Chardonnay, have what it takes to improve with maturity. Even then, variations in vintages and winemaking techniques will dictate different measures of longevity.

However, there are rare exceptions to the rule of young wine being pale. Most notably, the wines of Arbois in eastern France hold a gold color that comes from a combination of the Savagnin (not Sauvignon) grape and aging in wooden barrels.

In modern winemaking, white wines tend to have very little—if any—skin contact. That means, once the grapes are crushed, the skins are almost immediately removed—unlike in red winemaking, which relies on extended skin contact for enriching the wine’s pigment. In fact, if there were no skin contact at all, white wine would be colorless.

Alternately, nowadays, there’s a small but enthusiastic “orange wine” movement. Orange wine is the term used for white wine that is processed similarly to red wine. It’s allowed extended skin contact and as a result, develops a deep, orangey color. The results, flavor-wise, are very mixed. Though this method of processing white wine grapes is still on the fringes of winemaking, who knows what wine styles might evolve in the future?

Now, you can look at white wines and draw conclusions about the grapes from which they’re made and their comparative age. Next time, we’ll start pairing those wines.

Recommended book

The Wine Bible by Karen MacNeil

Share with friends