Tuberculosis

Episode #5 of the course “History of western epidemics” by Robin Tang

Tuberculosis has been around since the beginning of civilization. Written records show that it was present in the Greek and Roman Empires, and the bones of mummies have traced it back to ancient Egypt. Its upsurge in modern history coincided with the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, where it afflicted the crowded urban areas of the industrializing countries of northern Europe—for example, England, France, and Germany—much more than the predominantly agricultural societies of Spain and Italy.

Tuberculosis is mainly spread through the air as the sick cough and sneeze, expelling the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis in airborne droplets. The bacteria can spread to many organs in the body, but historically, the overwhelmingly dominant form of TB was pulmonary—commonly known as “consumption.” The onset of symptoms varied widely, with some patients dying within months of contraction, while others fell ill, went into prolonged remission, then relapsed without warning and suffered an early death. Before the discovery of antibiotics, around 80% of the cases led to eventual fatality.

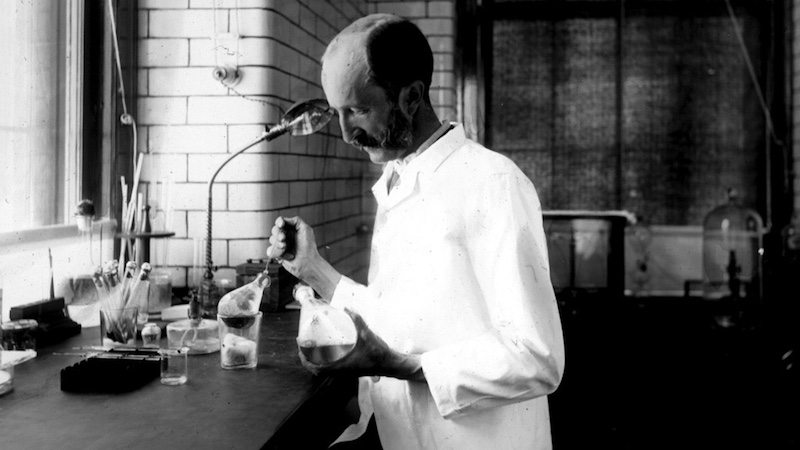

Since tuberculosis could lie dormant for years, it was not well understood as an infectious disease until Robert Koch identified the Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882 through his research on germ theory. Before this discovery, tuberculosis was regarded with an almost romantic allure thanks to its numerous references in literature (such as Wuthering Heights, Les Misérables, and La Bohème). René Laennec popularized this view through his essentialist theory, which suggested that the patient’s inherited essence predisposed him or her to TB. The emaciated pallor even became a new standard of feminine beauty, with healthy women losing weight and putting on white rice powder to imitate the consumptive look.

With the establishment of germ theory and advancements in public health awareness, tuberculosis became stigmatized as a “social disease” by the late 19th century. Scientific observations proved that TB was in fact contagious and was mostly spread among the poorly ventilated, crowded tenements of immigrants and the working class. Sanatoriums subsequently gained popularity as havens for the sick as well as quarantines from the healthy.

One of the most well-known sanatoriums was founded by Edward Livingston Trudeau, an American physician who had contracted TB himself. Following popular advice at the time, he went to Saranac Lake in upper New York state to recover in the open air of the wilderness. Upon feeling better, he established Little Red in 1884, where he allowed the sick to lead an outdoor life and adhere to a very substantial diet to combat the emaciation of the body. He estimated that Saranac Lake helped achieve a recovery rate of 30% among active cases of TB that previously would have likely resulted in death.

Recommended book

“The Remedy: Robert Koch, Arthur Conan Doyle, and the Quest to Cure Tuberculosis” by Thomas Goetz

Share with friends