The Technology of Precision Machinery

Episode #8 of the course Technologies that transformed humanity by Richard L. Currier, PhD

When the clockmakers of medieval Europe created precision machinery, they triggered an explosive growth in science and technology, a revolution in travel and trade, and an industrial economy completely dependent on the energy from fossil fuels.

The Clockmaker’s Genius

The Europeans of medieval times were a pious people who believed that prayers should always be said at exactly the correct times. The churches and monasteries of medieval times were all equipped with bell towers, and the bells rang whenever it was time to say prayers.

Since ancient times, people had kept time with sundials, water clocks, sandglasses, and burning incense, but those methods were all notoriously inaccurate. But shortly after 1200 AD, medieval craftsmen invented mechanical clocks that automatically rang the bells on time.

In order to run at a constant speed, mechanical clocks required geometrically precise parts. Their wheels, shafts, and cylinders had to be perfectly round and straight, and the teeth on their gears had to be exactly shaped and precisely spaced.

So, the medieval clockmakers created special “machine tools” capable of making objects more precisely than could be made by hand. Lathes made shafts perfectly straight and wheels perfectly round, drills bored perfect holes, and milling machines ground surfaces perfectly flat. Saws, grinders, planers, and shapers were guided by special devices mounted on rails or tracks.

With these new machine tools, the medieval clockmakers successfully built huge clocks that kept amazingly accurate time. Before long, like ripples in a pool, precision machinery began to affect every aspect of European society.

The Fruits of Precision Machinery

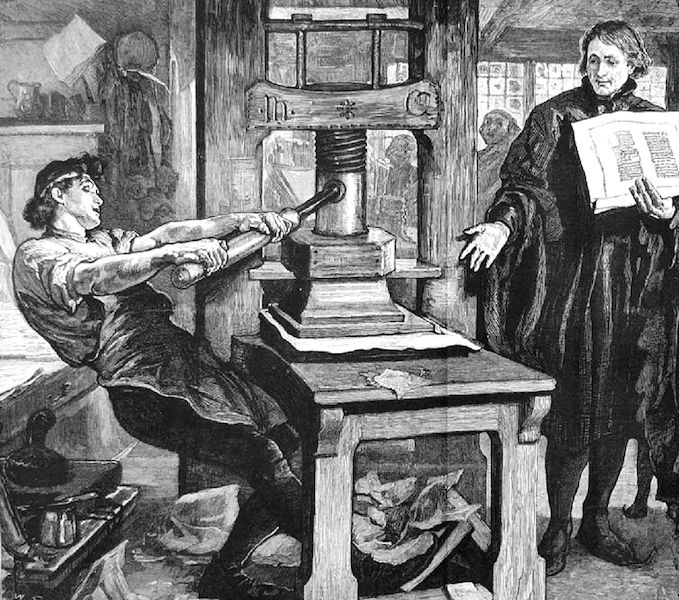

Precision lenses were created for telescopes that revealed the mysteries of the universe and for microscopes that revealed life-forms too small to see with the naked eye. Precision printing presses triggered an unprecedented dissemination of knowledge, resulting in the rebirth of science and literature known as “the Renaissance.”

Johannes Gutenberg used precision machinery to create a printing press with movable type, triggering an explosion of knowledge in Europe.

Precision sextants and compasses enabled seafarers to sail thousands of miles across the open sea, discovering new trade routes and exploring previously unknown lands. Firearms of every size, from cannons to pistols, were bored with precision barrels that immensely extended their range and accuracy, revolutionizing warfare.

How a New “Iron Age” Created the Industrial Revolution

Although the “iron age” technically began over 4,000 years ago, bronze actually remained civilization’s most popular metal well into the Middle Ages. Bronze was strong, easily smelted in ordinary furnaces, and resisted corrosion far better than iron. But the ores for making bronze were available only in certain locations and in limited quantities, while iron ore was plentiful almost everywhere.

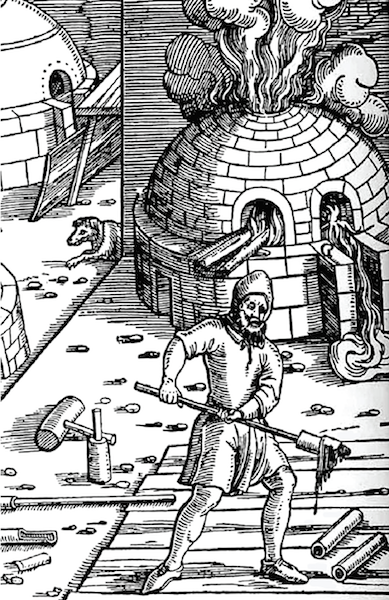

The gigantic clocks of medieval times were each fashioned from thousands of pounds of metal, and when hundreds of these clocks were being constructed, the demand for iron skyrocketed. The intense heat required for smelting iron required building wood-fired blast furnaces, and soon the forests of Europe began to disappear under the woodsman’s axe.

A wood-fired blast furnace of 16th-century Europe.

So, iron-workers turned to coal to fuel the blast furnaces. But as the coal mines went deeper, they became flooded with groundwater, and in the 1700s, giant steam pistons, moving slowly up and down, were built to pump out the water.

But when James Watt attached a flywheel to the steam piston, he converted reciprocating motion into rotary motion. The invention of the steam engine marked the first time in history that mechanical power became independent of the whims of wind, water, beasts, and men. Steam engines soon proliferated throughout the world, powering sawmills, flour mills, textile mills, and factories of all kinds.

Above all, the steam engine revolutionized transportation. The months-long voyage across the Atlantic by sail was reduced to two weeks by steamship. Trade routes that formerly took weeks on wagons or river barges shrank to days or hours by railroad. Finally, the internal combustion engine and the electric generator—which only existed because of precision machinery—spawned the automobile, the airplane, and electric power and laid the foundations of the modern age.

In tomorrow’s lesson, you will learn how the technology of digital information is revolutionizing human society once again, creating a world that no human society could ever have imagined.

Recommended reading

James Watt, Father of the Modern Steam Engine

Recommended books

The Discoverers: A History of Man’s Search to Know His World and Himself by Daniel J. Boorstin

History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders by Gerhard Dohrn-van Rossum

The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450-1800 by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin

Share with friends