Suprematism

Episode #6 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

Today we enter the “Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings: 0,10” of 1915 at the Marsovo Pole in St. Petersburg, Russia. The walls are sporadically scattered with geometric shapes and nonrepresentational designs. The crosses, rectangles, and circles that hang around you are monochromatic, opaque, and simplistic. Alongside these seemingly isolating works, the exhibition’s key figure Kazimir Malevich presents a scything manifesto, opening with the lines: “Only when the conscious habit of seeing nature’s little nooks, Madonnas, and Venuses in pictures disappears will we witness a purely painterly work of art.” This was the birth of Suprematism, one of the most radical approaches to abstraction that would put Russia on the modern art map.

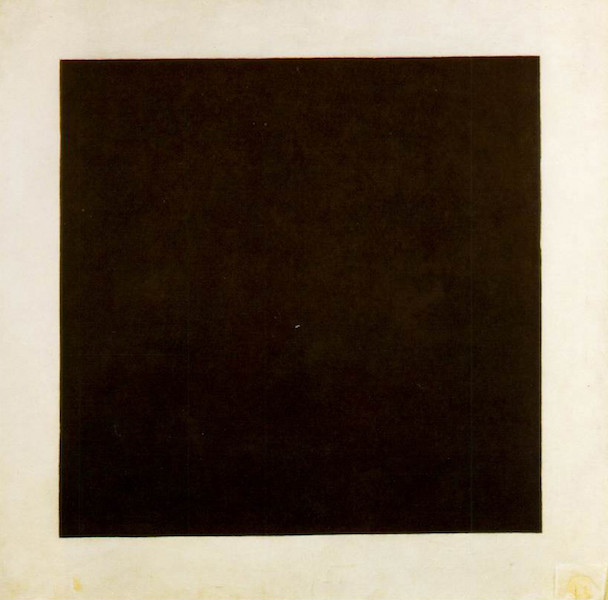

Kazimir Malevich. Black Square, 1915. Oil on canvas. 31.5” x 31.5”. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Malevich declared Black Square (1915) to be the first Suprematist painting, a shock of opaque black against a white canvas. For Malevich, representation and naturalism were but a means to approach an interior truth. He describes Suprematism as “the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling.” As such, the pure geometry and coloration of his work is a mystical resonation of emotion, coupled with an extremist belief in the superiority of art as “concept” over what is represented. It is the ultimate revolt against not just the value systems of Academic realism, but the avant-garde’s (and more particularly, Russia’s synthesized Futuro-Cubism of the early 1910s) relentless grip on naturalistic elements and reliance on the figurative, no matter how abstracted.

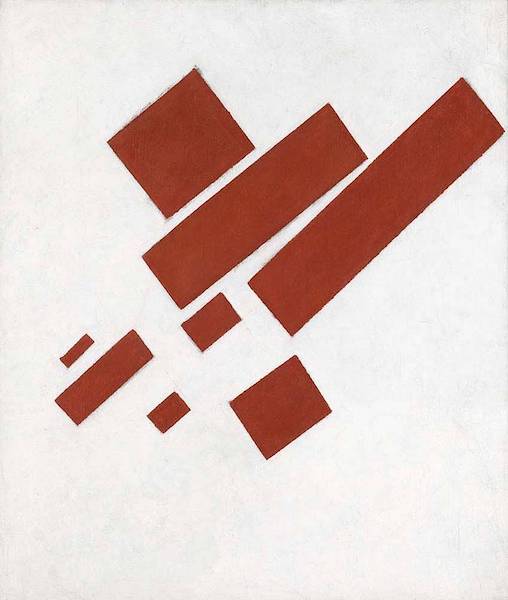

Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Painting, Eight Red Rectangles, 1915. Oil on canvas. 22.5” x 18.9”. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich, Dynamic Suprematism, 1915 or 1916. Oil on canvas. 31.6” x 31.5”. Tate Gallery, London.

Malevich went through three stages in his embarkation of total emotion through paint: black, colored, and white. Suprematist Painting, Eight Red Rectangles (1915), also displayed at the 0,10 Exhibition, is of this second stage. A mixture of diagonal rectangles of varying shapes, Malevich disturbs Western ideals of depth, perspective, balance, and nuance. During this period, Malevich would experiment with more variegated primary and secondary hues, off-putting layers, and peculiar arrangements of shapes, as evident in Dynamic Suprematism (1915/16). This increased interest in color specifically is better understood alongside Malevich’s statement in 1919: “New frameworks of pure colour must be created, based on what colour demanded and also that colour, in its turn, must pass out of the pictorial mix into an independent unity, a structure in which it would be at once individual in a collective environment and individually independent.”

Olga Rozanova. Suprematism, 1916. Oil on canvas. 35.4” x 29.1”. Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts, Russia.

El Lissizky. Beat the Whites with the Red Edge, 1919-20. Lithograph. 23” x 19”. Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands.

Though Malevich proclaimed the death of Suprematism in 1919, there were a handful of Supremus artists and advocators who incorporated his ideas into their own works. Olga Rozanova’s Suprematism (1916) provides a more textured method, and her colors and geometric placements are much more chaotic, thus paving the way for the shapes later portrayed by nonrepresentational artists such as Wassily Kandinsky. Meanwhile, El Lissizky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Edge (1919-20) deviates from Malevich’s absolutist stances to incorporate a subtle political stance, juxtaposing “traditionalist” white against a “radicalized” red. Nevertheless, the eschewment of pictorial representation aligns his work with Suprematist ideals.

In its brief four or so years of existence, Suprematism was able to reconfigure and revolutionize the Western traditions of art. Whether it be through Mondrian’s spiritual, De Stijl grids, Barnett Newman’s immense Color Field paintings, or Yves Klein’s minimalist monochromes, the impact of Suprematism would truly reign supreme in the following decades through a plethora of abstract artists. See you tomorrow for another thrilling installment of modern art.

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Share with friends