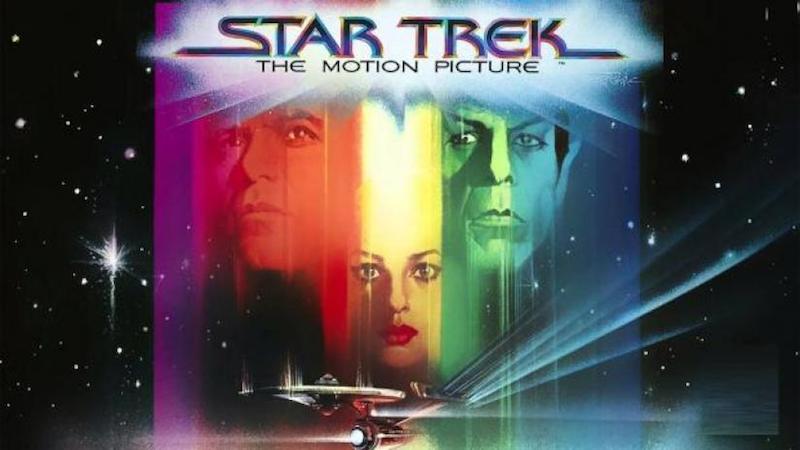

Star Trek: Does the Transporter Preserve Personal Identity? (Could There Be an Afterlife?)

Episode #5 of the course Sci-Phi: Philosophy through science fiction by David Kyle Johnson, PhD

I closed the last lesson by asking whether a genetically identical doppelgänger of you in an alternate universe would be “the same person” as you. In asking this, I am not asking whether they would be the same type of person as you; they might, they might not. An alternate universe could expose your doppelgänger to an extremely different environment, making them look, behave, and believe in completely different ways. The question is whether they would be (what philosophers call) numerically identical to you. Would they be the same object? Would they be “the same person” in the same way that you and your eight-year-old self are the same person?

Understanding Transporters (and the Question of Personal Identity)

The answer depends on what constitutes personal identity—what preserves it over time. And we can explore the possible answers to this question by thinking about the transporter technology from Star Trek.

Star Trek’s transporters work by disassembling a person’s body, atom by atom, and then reassembling it in a different location. The characters in Star Trek, like Spock, use transporters to “beam down” to alien planets. But the question is this: Is the person who steps into the transporter (Spock1) really the same person as the one who appears on the planet (Spock2)? Sure, they look and act the same—but are they numerically identical? Is a transporter really a transporter? Or is it just a suicide/copy machine?

Is It Your Soul? Your Memories?

One might think that the answer to this question depends on whether Spock2 has the same soul as Spock1. But there are two problems with this answer. (A) Most philosophers reject the idea that souls exist; our mental activity is not housed in a separable non-material substance but is instead produced by and dependent upon brain activity. And (B) having the same soul is not necessary for preserving personal identity. If two people switched souls without switching minds, you wouldn’t even be able to tell that anything happened.

John Locke would have suggested that Star Trek transporters preserve identity because they preserve memory: Spock2 remembers being Spock1. But memory doesn’t seem to be necessary for preserving identity either. If I can’t remember my wife driving me home from the dentist after getting a tooth pulled, that doesn’t mean that it wasn’t me whom she drove home. Memory doesn’t seem to be sufficient either. What if Spock1’s atoms are lost and the transporter uses a different set of atoms to construct Spock2. Spock2 would remember stepping into the transporter, but he wouldn’t actually be Spock1. Because he’s made of different material, he’d just be a copy.

Same Body? No Afterlife?

This generates a new theory. Maybe being made of the same atoms is what preserves identity. This (like Spock) seems logical. But it also causes two problems. First, by this criterion, you are not even the same person as your eight-year-old self. As we grow and live, we shed the cells that make up our bodies and use the matter we ingest to create new ones. Over a roughly seven-year period, all the matter in your body is replaced. So, you do not now have the same body as your eight-year-old self.

Second, this theory would seem to make an afterlife impossible. Since when you die, the atoms that make up your body are either buried or cremated and eventually re-enter the ecosystem—apart from God secretly snatching and repairing your body before you die (as Peter van Inwagen once suggested)—it doesn’t seem possible for you to survive into the afterlife. God, of course, could create someone who looks and acts like you in heaven, out of new material (as John Hick suggested), but that would only be a copy of you.

Reconceiving Persons

All these difficulties have promoted some philosophers, like David Lewis, to completely reconceive what a person is. Instead of a person being something that exists at a particular place and time, perhaps persons are four-definitional objects stretched across time held together by bodily and psychological continuity (i.e., gradual changes in body and mentality) preserved by a proper causal connection. This view is called perdurantism.

If it’s correct, the question isn’t whether Spock1 and Spock2 are the same person, but whether they belong to the same set. The answer would seem to be yes, and we could give the same answer regarding your current and eight-year-old self. We might even be able to do the same regarding your doppelgänger in an alternate universe and even some person God creates in the afterlife. Indeed, we might even be able to guarantee our own survival beyond death by discovering how to upload our mentality into an android.

But this leads us to our next topic: artificial intelligence. Could artificial beings, like androids, one day be capable of housing minds? Could they be conscious? Self-aware? Sentient? To explore these questions next lesson, I want to talk about the popular HBO series, Westworld.

Recommended reading

“The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Personal Identity” by Carsten Korfmacher

“The Possibility of Resurrection” by Peter van Inwagen

Recommended books

The Ultimate Star Trek and Philosophy: The Search for Socrates edited by Kevin S. Decker

“Resurrection of the Person” from Death and Eternal Life by John Hick

Share with friends