Spanish Flu

Episode #6 of the course “History of western epidemics” by Robin Tang

The annual flu season is familiar to most people, but a particularly virulent strain of the influenza virus has become somewhat of a “forgotten pandemic.” The Spanish Flu of 1918-1920 infected roughly a third of the world’s population at the time, killing an estimated 50-100 million people. In the U.S. alone, roughly 675,000 people died from the disease—more than 10 times the casualties in World War I.

Despite its name, the Spanish Flu did not in fact break out in Spain. Its true origin is still debated among historians, but most now believe that the first cases in Europe were observed in France, while the first American cases were reported in Fort Riley, Kansas in the spring of 1918. Spain had the misfortune of being affiliated with the epidemic because it remained neutral during WWI and freely reported cases of the outbreak, while both sides of the war severely censored their media in an attempt to prevent news of the spread from affecting wartime morale.

One of the most distinctive features of the 1918 epidemic was its predilection for healthy young adults. Most strains of influenza killed infants and the elderly at a much higher rate, exhibiting the typical U-shaped graph of death by age group. The Spanish Flu, in contrast, produced a W-shaped curve. The death rate for people between 15 and 34 years of age was 20 times higher than that of previous flu outbreaks.

Scientists have since discovered that the Spanish Flu triggered an overreaction of the immune system, thus making the young and healthy particularly vulnerable. For example, a U.S. pentathlon champion named John Hellum died from the disease in the fall of 1918. A staggering 2.5% of infections resulted in death, compared to the usual flu fatality rate of under 0.1%.

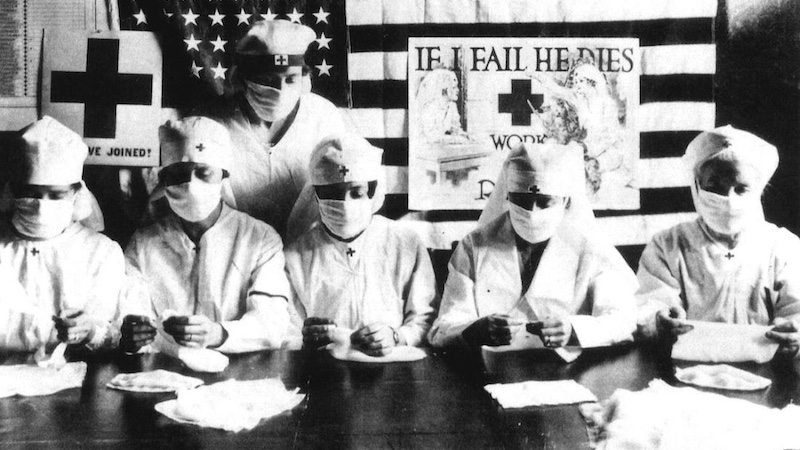

The combined high morbidity and mortality of the Spanish Flu produced perhaps the greatest demographic shock from any infectious disease. The shortage of doctors and nurses as a result of WWI also put great strains on the public health system. Its only saving grace was that it disappeared almost as quickly as it appeared. The last cases were reported in January and February of 1920, when it had already mutated to a much milder virus.

Recommended book

“The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History” by John M. Barry

Share with friends