Post-Impressionism

Episode #2 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

As we learned, the Impressionists set the stage for modern art by subverting realistic representation and mythological or religious subject matter, instead favoring “slices of life” and utilizing painterly blurs, broken colors, and “fleeting” brushstrokes. But by the 1880s, the creative boundaries Impressionism had set started to broaden, and thus new questions emerged: if art can depict the experience of vision, can one also represent the burgeoning theories of subjective optics and color, or even the artist’s psyche? How can other formal and structural qualities other than brushstrokes provide expression beyond a work’s subject matter? Today we will explore the artwork of four idiosyncratic figures who challenged the confines of art even further, providing the launchpad for 20th-century movements.

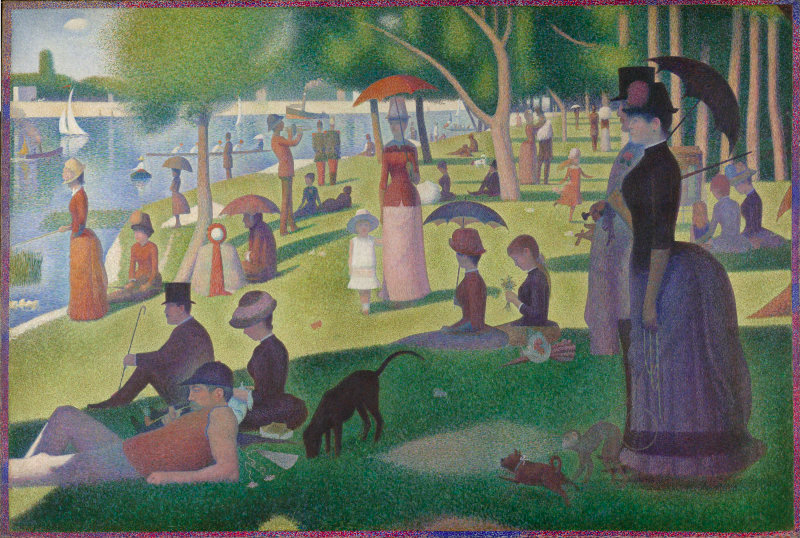

Georges Seurat. Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte, 1884-86. Oil on canvas. 6’ 9.5” x 10’ 1.25”. Art Institute of Chicago.

Georges Seurat was one of the first to distinctively break away from the Impressionist movement, presenting his magnum opus Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte (1884-86) at the group’s final exhibition. Seurat introduced his pointillist technique, placing pure colors side by side in divided, miniscule dottings to create a larger image. From afar, the painting depicts a typically Impressionist setting but with bolder, structured hues; however, as the viewer moves closer to the canvas, the complementary hues begin to abstract. This scientific and theoretically dense experimentation with optics and “color vibrations” was described by Seurat as “Neo-Impressionism,” his concepts influencing several contemporaries.

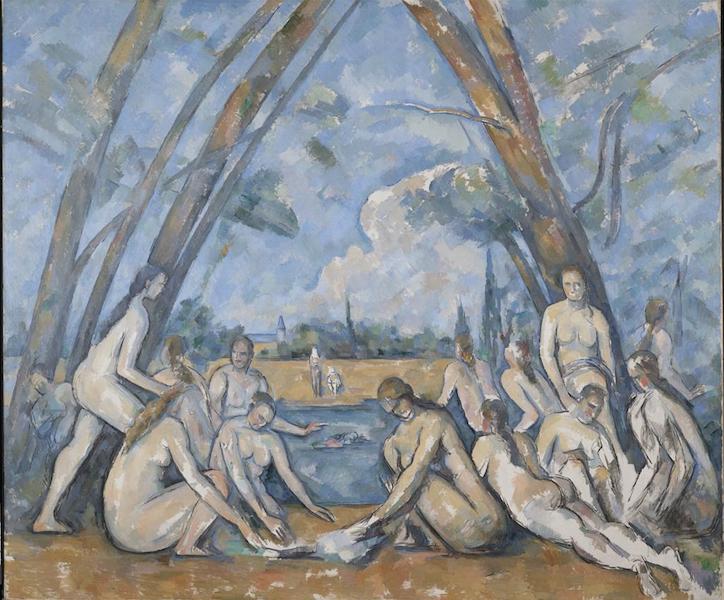

Paul Cézanne. The Large Bathers, 1906. Oil on canvas.82.65” x 98.1”. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Like Seurat, Paul Cézanne was interested in the construction of space and volume on the canvas; yet, instead of focusing on evocative color theory, Cézanne focused on geometric shapes and bold, structured outlines. In The Large Bathers (1906), Cézanne presents a modern rendition of the classical nude figure, the seemingly unfinished bodies and stucco-like skin preceding the deconstructed abstraction Cubists would master in the upcoming years. His brushstrokes are equally as intriguing, offering a patchwork of textures and hues that simultaneously evoke flickering movement and serene stillness. This palette, as well as the thick impasto application of paint, deeply disrupted Western spatial conventions.

Vincent Van Gogh. The Starry Night, 1889. Oil on canvas. 29” x 36.25”. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

Other Post-Impressionist artists, such as Vincent van Gogh, were concerned with manipulating formal elements as a means of expressing the inner self. The swirling, emphatic linework and luminary, effervescent color juxtapositions in The Starry Night (1889) offer a peek into the chaotic psyche that informed much of van Gogh’s approach. And yet his virtuosic technique suggests a true proficiency in texture and balance, the expressive, dash-like brushstrokes complementing the twirling, spirited atmosphere. Most critically, van Gogh achieves an emotional space that is more resultant of his formal methods than his choice of subject matter.

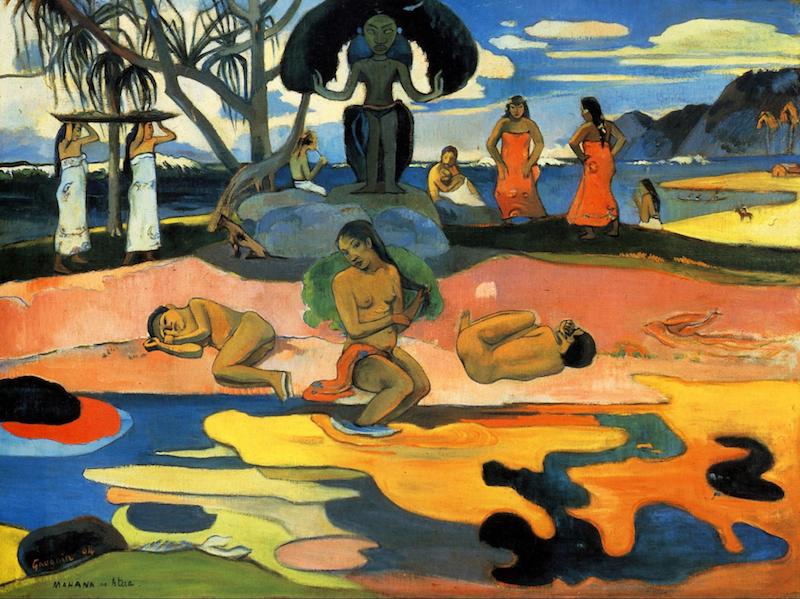

Paul Gauguin. Day of the Gods (Mahana No Atua), 1894. Oil on canvas. 26.75” x 36”. Art Institute of Chicago.

Paul Gauguin would take van Gogh’s proto-Expressionist ideas to the limits of the imagination, countering the Impressionists for their focus “around the eye and not at the mysterious centre of thought.” Reviled by the urbanization and industrialization of Western civilization, Gauguin moved to Tahiti for two years, reflecting a growing interest in what was described as primitive art and lifestyle. His piece Day of the Gods (1894), though exoticizing the country and minimizing its colonialist struggles, presents a colorful, congruous beach scene. The most captivating aspect is the pools of darkly contoured, saturated hues, adding a poignant intensity to the painting’s mood. The central deity hovers over three women, representing the cycle of birth to death and adding stability to this otherwise radical piece.

Each of these artists therefore offered a unique insight into the potentialities of modern art and would be visually quoted in the following decades through a variety of avant-garde “-isms.” Join us tomorrow as we venture closer toward the turn of the century, and thus closer to the revolutionary movements that Post-Impressionism inspired.

Share with friends