Pop Art

Episode #9 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

In the early 1950s, the Abstract Expressionists eschewed both propagandistic kitsch and High Modernist tastes, instead favoring the very action of artistic creation in hopes of capturing the unbounded vitality of the artist. Though these works reflected grand ideals of expressive freedom and visceral energy, these highly subjective, esoteric drip paintings came to represent the out-of-touch bourgeois establishment the artists initially refuted. This movement also paralleled the rise of visual culture and American globalization, during which consumerism and capitalism ran rampant. As such, an interest in the material world emerged, and with it, a new artistic movement: Pop Art.

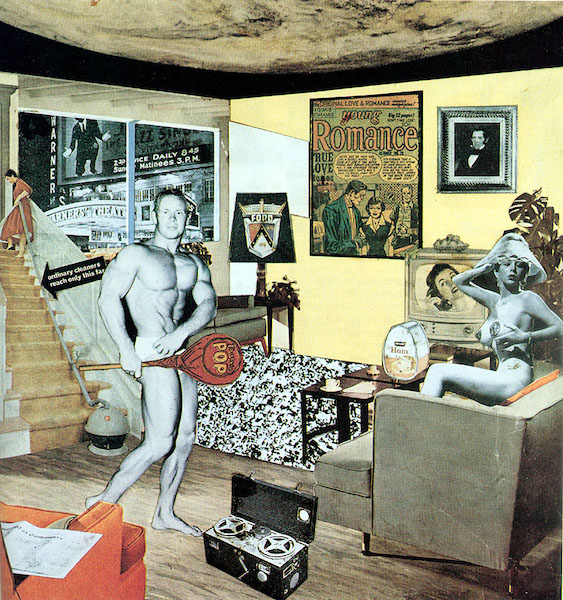

Richard Hamilton. Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, 1956. Collage. 10.2” x 9.85”. Kunsthalle Tübingen, Germany.

The origins of Pop Art can be traced back to London’s Independent Group, an avant-garde collective that analyzed the role of art in a mass media consumer society. Borrowing techniques from Dadaism such as collage and irony, Richard Hamilton’s Just What Is It That Make’s Today’s Homes so Different, So Appealing? (1956) provides a critique of frivolous consumption by utilizing the same techniques of mainstream advertising. The domestic space is rampant with decadence and visual media, while the body builder and exotic dancer offer hypersexualized representations of gender. These concerns are epitomized by the phallic and punning Tootsie Pop. Though wrapped up in commercialized graphics, Hamilton’s collage still speaks back to art history, evoking a modern-day Adam and Eve that echoes the idealism of Greek sculpture.

Robert Rauschenberg. Bed, 1955. Oil and pencil on pillow, quilt and sheet on wood supports. 75.25” x 31.5” x 8”. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

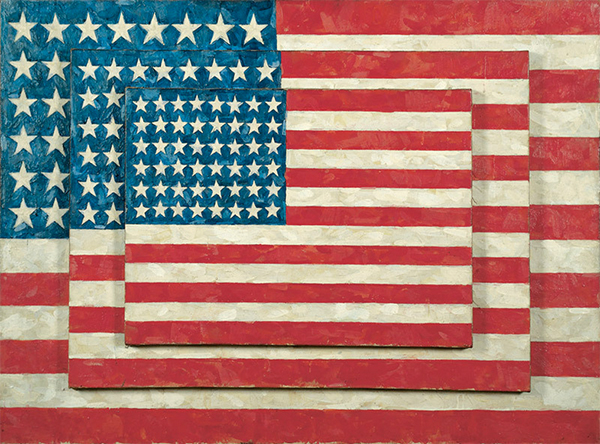

Jasper Johns. Three Flags, 1958. Encaustic on canvas. 30.6” x 45.5” x 4.6”. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Across the Atlantic, American artists were also beginning to experiment with everyday objects and symbols to provoke new ways of engaging with mundane modernity. For example, Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955) defamiliarizes the commonplace bed by splattering it like an action painting. But unlike his Abstract Expressionist predecessors, Rauschenberg’s first “combine,” like Duchamp’s assemblage pieces, brings material, found objects to the forefront, reintroducing the importance of externality over internal rumination.

Jasper Johns’ Three Flags (1958) is similarly concerned with the balance between the abstract and the representational. His encaustic technique emphasizes his artistic manipulation of the flag, allowing the viewer to enter the work as more than symbolic—in Johns’ words, to be “looked at” and not merely “seen.”

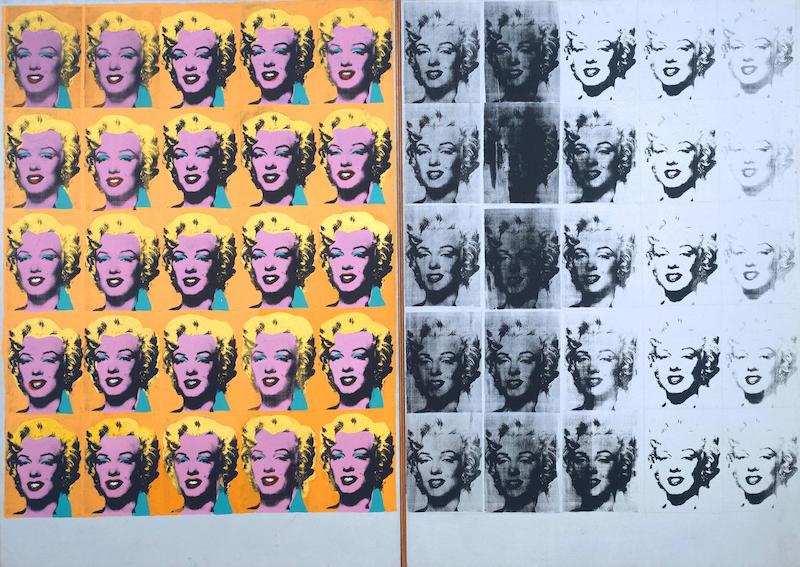

Andy Warhol. Marilyn Diptych, 1962. Oil, acrylic, and silkscreen on canvas, two panels. 80.9” x 9’ 6”. Tate Gallery, London.

By the 1960s, Pop Art was all the rage in the States, and Andy Warhol encapsulated its ethos, both through his lifestyle and art. His studio, The Factory, became a hub for avant-garde artists and celebrities alike, and his mass-produced silkscreen approach destabilized the artists’ relationship to their work, reimagining the artist as a machine and rejecting the idea of art as personal expression. Marilyn Diptych (1962) is a quintessential example of Pop Art’s interest in appropriation and celebrity, reproducing a Monroe publicity photo multiple times to represent her omnipresence in society. The bright coloration of the left panel contrasts with the faded grayscale portraits on the right, which some critics have read as a juxtaposition between Monroe’s idolized status and her mortality—indeed, 1962 was the year she overdosed on barbiturates. The diptych structure also elicits religious connotations, portraying Monroe as a martyr.

Roy Lichtenstein. Whaam!, 1963. Acrylic and oil on canvas. 66.9” x 13’ 4.8”. Tate Gallery, London.

Combining the ideas of Johns and Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein’s “comic book paintings” appropriate popular media and expand its scale on canvas, allowing viewers to examine these works more thoroughly. The subject matter of Whaam! (1963) not only disrupts the hierarchy of “high art” by heightening the artistic weight of mass-produced images, but it also gives a subtle pun on Lichtenstein’s approach to “blowing up” his primary sources. As Lichtenstein points out, “Pop Art looks out into the world. It doesn’t look like a painting of something, it looks like the thing itself.”

While Pop Art made critical statements regarding consumer society, visual media, and technological advances, it was largely disregarded by the general public, and by the early 1970s, less tangible forms such as Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art would dominate the art world. Check in tomorrow to find out more about how these growing art movements emerged.

Share with friends