Pluto

Episode #9 of the course Introduction to the Solar System

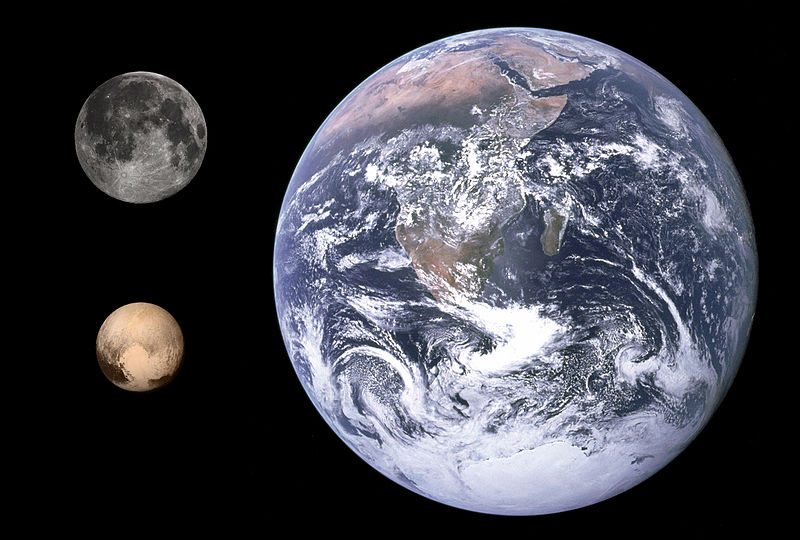

At one time, Pluto was known as the ninth planet in our solar system—until it was demoted to dwarf planet due to a technicality. In 2015, NASA’s New Horizons mission visited Pluto to take measurements, which determined that while Pluto is larger than previously thought (with a diameter of 1,473 miles or 2,370 kilometers), it is not large enough to be classified as a full-grown planet. As the farthest (dwarf) planet from the Sun, the average surface temperature hovers around negative 230 degrees Celsius (-382 degrees Fahrenheit). For most of its seasons, Pluto is coated in a thick layer of ice that releases nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide—the three components of Pluto’s atmosphere.

Size comparisons: Earth, the Moon, and Pluto

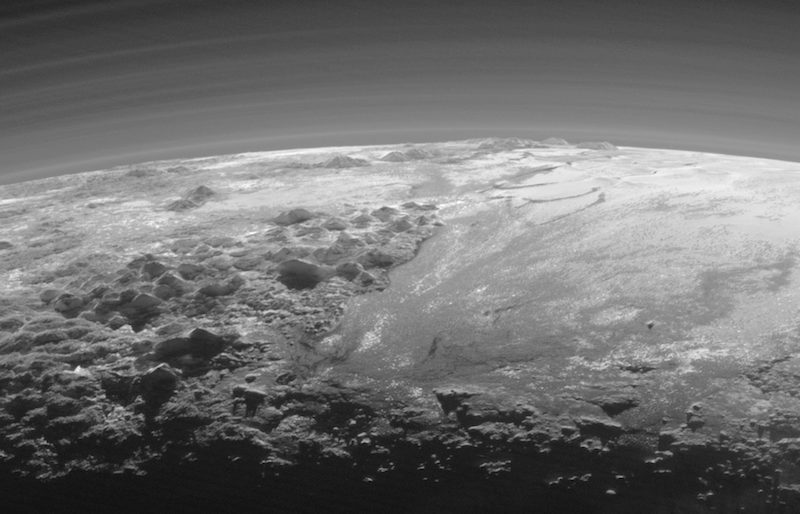

Majestic Mountains and Frozen Plains: Just 15 minutes after its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft looked back toward the sun and captured this near-sunset view of the rugged, icy mountains and flat ice plains extending to Pluto’s horizon. The smooth expanse of the informally named Sputnik Planum (right) is flanked to the west (left) by rugged mountains up to 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) high, including the informally named Norgay Montes in the foreground and Hillary Montes on the skyline. The backlighting highlights more than a dozen layers of haze in Pluto’s tenuous but distended atmosphere. The image was taken from a distance of 11,000 miles (18,000 kilometers) to Pluto; the scene is 230 miles (380 kilometers) across.

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Pluto spins in retrograde, meaning that the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east. The planet also spins slowly, with one full rotation of Pluto taking approximately 6.39 days on Earth.

Five satellite moons orbit around the dwarf planet: Charon (1978), Nix (2005), Hydra (2005), Kerberos (2011), and Styx (2012). The moon Charon, which is half the size of the dwarf planet, is located 12,160 miles (19,570 km) from Pluto, but the two are in a gravitational lock. That means that regardless of the time of day, the same face of Pluto is facing Charon and vice versa. Though Charon is currently considered a moon, there is no true orbit of either object around the other, and scientists are considering Charon’s classification as a dwarf planet sometime in the future.

Pluto and Charon as viewed by New Horizons (natural color; July 11, 2015)

While Pluto is known for being the farthest planet from the Sun, there is a moment in time when it actually swaps places with Neptune. This is when the two orbital paths cross over one another and Neptune swings out farther in space than Pluto. In fact, between 1979 and 1999, Neptune was farther from the Sun than Pluto; however, this rare phenomenon only occurs for a 20-year period once every 248 years. Because the two planets don’t physically cross near one another, Pluto is never subject to Neptune’s gravitational pull, and the two could never collide.

After the discovery of Neptune, astronomers observed irregularities in the orbit of Uranus, and several hypothesized that an additional unknown planet was awaiting detection. On February 18, 1930, astronomer Clyde W. Tombaugh, a 24-year-old man working at an observatory in Arizona, discovered what would become the ninth planet in our solar system.

From February 1930 to August 2006, Pluto enjoyed planetary status, though there was dissention among the scientific community regarding whether or not it deserved that designation. Then, in August 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) agreed that Pluto should no longer be considered a planet and would instead take on the title of dwarf planet. Dwarf planets are classified by NASA as those celestial objects that are in direct orbit of the Sun, are not moons, are massive enough for their gravity to crush themselves into a round shape, and have not cleared the neighborhood of other material around their orbits. When astronomers discovered that Pluto was sharing space on the Kuiper Belt, Pluto’s reclassification took effect, though the debate rages on.

Recommended book

“A Little Book of Coincidence” by John Martineau

Share with friends