Performance Art

Episode #10 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

In 1909, Futurist founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti issued a manifesto outlining the goals of his avant-garde art movement, declaring, “We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.” This utterance planted the seed of the art movement that would come into international prominence approximately 50 years later. Like Futurism, performance art involves an “energy and rashness,” yet it explodes off the canvas and through the body. And, unlike theater, performance is not a repeated action that occurs on a fixated stage; rather, the site of performance is the presence/absence of the corporeal self, replacing the importance of form with concept. Though rooted in the manifestos and performances of the 1910s, performance art is simultaneously a rebellion against the artistic, cultural, and political barriers presented by Modernism—a rebellion we will further explore today.

Performance art emerged in several areas across the world. In America, the innovations of post-war performance philosophies are linked to the Abstract Expressionists, whose action paintings were notably described by prominent art critic Harold Rosenberg as “not a picture but an event.” Other artists, such as composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham, began to remove the event from the canvas by incorporating chance, commonplace, and mundane sounds and actions into their pieces. This resulted in compositions such as Cage’s “4.33”, which blurs the lines between space and time, as well as art and life. In Cage’s performance, the listener becomes aware of not just the ambient noises of the everyday, but their very presence as an audience. Its reliance on aleatory methods also makes it irreplicable in its “presentness,” laying out the foundation for performance art as we recognize it today.

Allan Kaprow. Fluids, 1967. Beverly Hills, CA.

Allan Kaprow was one of Cage’s protégés, and in 1957 he developed the term happenings, which Kaprow describes as “events that, put simply, happen.” In Fluids (1967), Kaprow arranged for 30 rectangular ice sculptures to be constructed around Pasadena and Los Angeles by random participants, which were thereafter left to melt. Kaprow’s happening not only breaks the barrier between artist and spectator, but also disrupts the permanence of the traditional art piece.

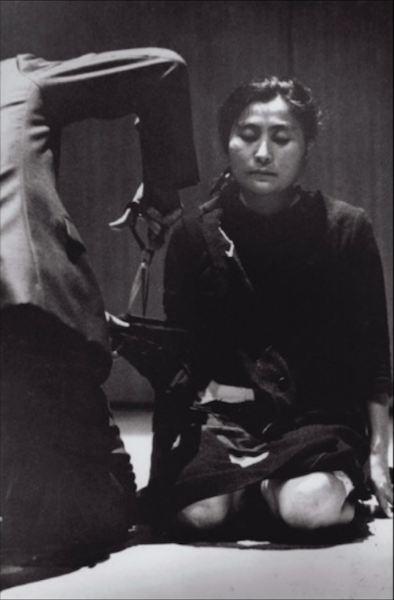

However, not all performance art is necessarily playful; it can also be political. For example, Fluxist artist Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece provides a striking statement on the representation of female bodies throughout art history. Ono invited audience members to cut pieces of her clothing as she kneeled passively on stage, implicating the audience in the aggressive act of exploitation. Ono’s performance, along with the civil rights and second-wave feminist movements, recognized the body as political, thus opening up space for critical dialogue.

Yoko Ono. Cut Piece, 1964. Yamaichi Concert Hall, Kyoto, Japan.

Performance art often works to affect the viewer with its very presence, whether it be to shock or disturb the audience or move them to critical action. This can result in vulgar, disturbing, and dangerous behavior. From Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971) to Vienna Actionist Hermann Nitsch’s gory and ritualistic Orgien Mysterien Theater, the distinction between artwork and reality can become unsettlingly vague. Joseph Beuys’ I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) is one of several of his “actions,” which he believed had the ability to self-heal and transform society. Beuys was transported from airport via an ambulance to the René Block Gallery in New York, where he remained caged with an untamed wolf for several days. A biting critique of US imperialism, colonialism, and the nature/culture divide, Beuys refused to touch American soil.

Joseph Beuys. I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974. René Block Gallery, New York.

Interest in this medium was rejuvenated in the 21st century by legendary performance artist Marina Abramović and her rousing performance at the MoMA, The Artist is Present (2010). Abramović invited gallery-goers to sit with her silently for as long as they pleased, resulting in a moment of emotional and spiritual transcendence.

Share with friends