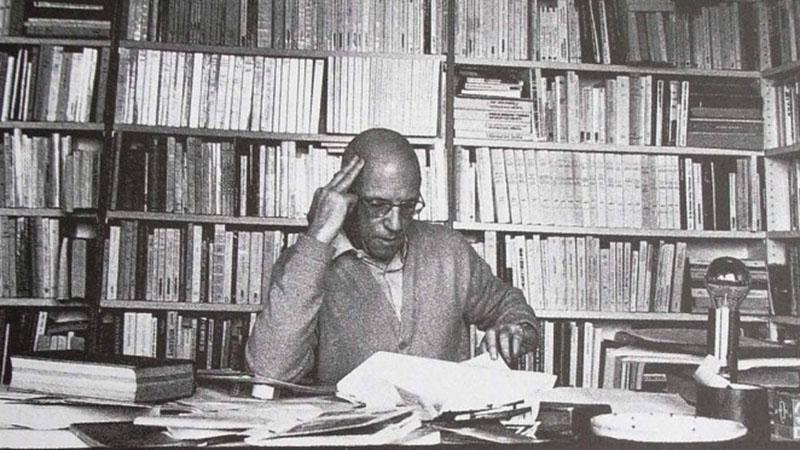

Michel Foucault

Episode #4 of the course Great modern philosophers by Tom Butler-Bowdon

In a nutshell: Every age makes unconscious assumptions about how the world is ordered, making the flavor of knowledge quite different from one era to another.

The Order of Things (1966) was the book that made Foucault a famous intellectual in France. Subtitled “an archaeology of the human sciences,” it attempts to show how knowledge is a cultural product, with different disciplines simply being expressions of the prevailing worldview.

Foucault’s basic idea is that each era, or “episteme,” is redolent with a “positive unconscious,” a way of seeing the world that it is quite unaware of. Our linear minds are used to taking a particular discipline, such as biology or economics, and seeing it as one evolving area of knowledge from its earliest conceptions up to the present day. But this does not reflect reality. The way that people saw the science of life (biology) in the 17th century, Foucault says, has more in common with the way they saw wealth and money in that era than it has with 19th-century biology. Each episteme is culturally contained and does not “lead” into another episteme.

Constructing Categories

The book arose in Foucault’s mind when he was reading a Borges novel and laughed out loud at a passage that refers to a Chinese encyclopedia that divides animals into: “(a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off ‘look like flies.’”

The weirdness of Borges’ list comes from there being no order of linkage between the things listed, no “ground” of knowledge. Which leads to the question: What is the ground on which our own categories rest? What is it we assume to be true or not true, linked or not linked, in our culture and time? Foucault suggests that not only do we not perceive anything objectively, our systems of categorization are assumptions, received and accepted unconsciously.

On an archaeological dig, you are not looking for a particular person, Foucault observes, but want to know how a whole community lived and what it believed. One looking at Swedish naturalist Linnaeus, for instance, is not enough to outline his discoveries—one must understand the intellectual and cultural “discourse” that allowed them to be expressed and taken note of—that is, the “unspoken order” of the times, the fundamental codes of a culture: those governing its language, its schemas of perception, its exchanges, its techniques, its values, and the hierarchy of its practices.

Foucault sets out to do this by investigating the threshold between Classical knowledge (knowledge prior to the 16th century) and the thinking and knowing that has come to constitute modernity. He studies art (Velasquez’s painting, Las Meninas) and literature (Don Quixote), as a prelude to analyzing three areas: language, economics, and biology.

If you are to write any kind of history that involves opinions, beliefs, prejudices, and superstitions, Foucault says, “what is written on these subjects is always of less value as evidence than are the words themselves.” To find out what people really thought in any given era, it is not the content, but how they say it and making what assumptions that gives us insights. We think of the sciences as having an objective reality, but Foucault describes them as being simply “well-made languages.”

Final Word

Foucault’s notion of epistemes is not that different to Thomas Kuhn’s “paradigms” of scientific thinking, and it is interesting that Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions came out just four years before Foucault’s—perhaps evidence that knowledge comes in the form of particular worldviews of which the individual is barely aware. Both books are an antidote to the conceit of current knowledge, and the belief in a linear model of knowledge accumulation. In reality, whatever constitutes the ground of knowledge in any field is wont to suddenly open up and swallow everything, with new forms of “knowing” springing up in a completely different place.

Tomorrow…Martin Heidegger and the nature of being.

Recommended book

The Order of Things by Michel Foucault

Share with friends