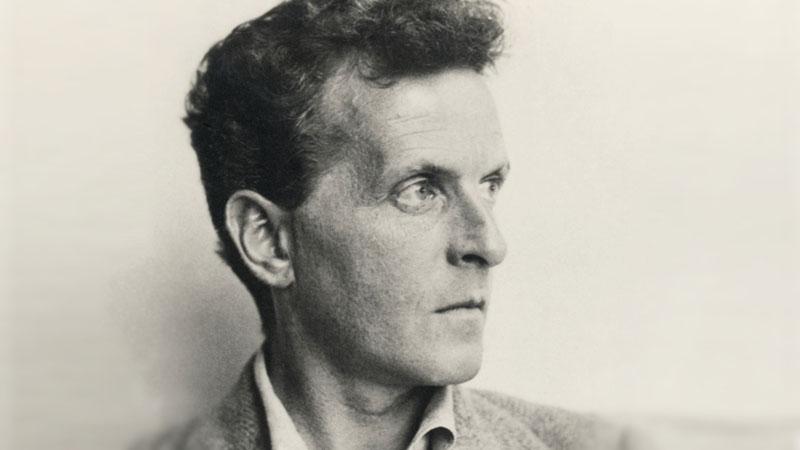

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Episode #10 of the course Great modern philosophers by Tom Butler-Bowdon

In a nutshell: Language is about meaning, not words. Yet language cannot express every kind of meaning.

When Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was published in German in 1921 and in English in 1922, he believed he had brought an end to philosophy, and left the academic world. He gave away all his money to his siblings (he was the eighth child in a wealthy Viennese family), worked as a primary school teacher in a mountain village, gardened in a monastery, and designed a house for his sister (to incredibly exacting measurements). He did eventually return to academia in 1929, taking the post of professor of philosophy at Cambridge University.

If the Tractatus is the doctrinaire, almost forensic work of a younger man, Philosophical Investigations (1953), published after his death, is more well-rounded and readable. A key line in the first book is, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” In the second, Wittgenstein shifted to say that language is not a formal logic that marks the limits of our world; it is a free-flowing, creative means for making our world. The depth and variety of our language-making is what separates us from other animals: “Commanding, questioning, recounting, chatting, are as much a part of our natural history as walking, eating, drinking, playing.”

Actual words spoken often mean less than the way they are spoken and the line of speech as a whole. When we ask someone to bring us the broom, we don’t phrase it in terms of, “Please bring me the stick with the brush attached to it.” Language does not break things into logical pieces but, if anything, works to make representation of actual objects unimportant next to their intended use. A word does not exist on its own but is part of a “family of meanings.” Wittgenstein goes to great lengths to identify what we mean when we say the word “game.” He thinks of all the possible kinds of games (board games, sports, a child playing, etc.) and yet is unable to say exactly what a game is and what it isn’t. And yet, we all know what a game is. This should tell us that definitions don’t matter next to meaning, or to put it another way, language does not dictate the limits of our world. It has no hard-and-fast rules, no objective logic as philosophers had hoped to identify. Language is a social construction, a game where the order of play is loose and evolves as we go along.

Wittgenstein did not try to deny that we have inner lives, only that they could not be spoken of sensibly. Even though the “language-game” is of extraordinary depth and complexity, there are areas of experience that can never be expressed properly in language, and it is wrong to try to do so.

A famous line in the book is, “If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.” Language depends on common assent of meaning, and animals naturally have a wholly different order of what things mean. A lion, for instance, sees someone walking through the savannah not as a “person,” but a potential source of food. Without agreeing on what things mean, how could we have a conversation with a lion, even assuming it could talk?

Final Word

Wittgenstein was influenced by William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience, the philosophical Christianity of Kierkegaard, and the writings of Augustine; despite his largely Jewish ancestry, he was brought up a Catholic. During war years, he could not be separated from his Bible, and he loved visiting churches and cathedrals. In a memoir, his Cambridge friend, M. O’C. Drury, reported him as saying:

“If you and I are to live religious lives it must not just be that we talk a lot about religion, but that in some way our lives are different.”

When Drury had doubts about his training as a doctor, Wittgenstein told him not to think of himself, only the good he could do. What a privilege, he pointed out, to be the last one to say goodnight to patients at the end of the day! Though important to him, Wittgenstein saw his work as just another game; language and philosophizing were nothing next to life itself.

And this concludes our final lesson. Thank you for taking this course!

Recommended books

Philosophical Investigations by Ludwig Wittgenstein

Share with friends