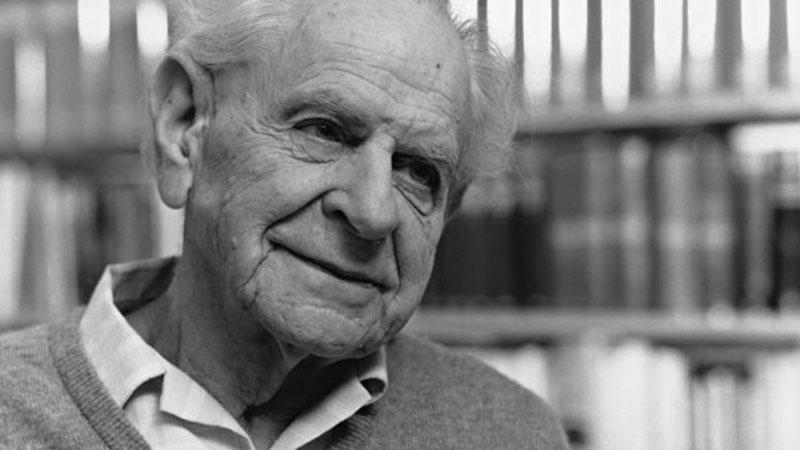

Karl Popper

Episode #8 of the course Great modern philosophers by Tom Butler-Bowdon

In a nutshell: We advance in understanding not by “proving” theories, but by attempting to falsify them.

When Logik der Forschung was published in Vienna in 1934, Karl Popper was only 32 and working as a secondary school teacher—slightly surprising, given the book’s huge influence on 20th-century thought. The Logic of Scientific Discovery (as the title was translated in 1959) put the philosophy of science on a firm footing, and figures such as Imre Lakatos, Paul Feyerabend, and Thomas Kuhn followed in its wake.

The Logic of Scientific Discovery was a reaction against the language-analyzing philosophy spawned by the Vienna Circle and typified by Wittgenstein, who had famously not even read Aristotle, believing that all philosophical problems could be solved through looking at language alone. Popper believed that the purpose of philosophy was to bring clarity to real world problems; it must seek to tell us something about our place in the universe. However, unlike engineering or some branch of physical science in which you know what the problem is and you go to work on solving it, philosophy has no “problem-situation”—there is no groundwork of accepted facts onto which a new question can be placed. Therefore, he said, “whenever we propose a solution to a problem, we ought to try as hard as we can to overthrow our solution, rather than defend it.”

The Problem of Induction and Its Alternative, Falsification

Popper saw a giant hole in philosophy and science: inductive thinking. Inductive statements take a particular and from it, assert something universal. For example, from the observation that all the swans we have seen are white, we assert that “swans are white.” But we only need one case where this is not true (as for instance, when black swans were discovered in Australia) to realize that inductive reasoning is faulty.

For a theory to be considered genuinely scientific, it must be able to be proven wrong—falsified by anyone and with results that are reproducible. It is totally wrong to believe that your theory is “proven,” “verified,” or “confirmed” if you can merely collect enough cases that seem to show it is true. A theory is not a real one is if there is no way of testing it to see if it is false. Further, because he does not believe in induction, Popper says that theories are never ultimately and conclusively verifiable, they are only “provisional conjectures” that can find apparent corroboration. Popper admits that it may seem wrongheaded to go about science in a negative, falsifying way, but notes that scientific laws tend to have credibility when it is clear where they do not apply, or as he puts it, “the more they prohibit, the more they say.”

From these arguments, you begin to see how Popper raised the bar on science, separating nice ideas from bona fide theories. Yet he did so only because he believed in the scientific project. The fact that it is hard, even impossible, to ever arrive at total certainty should not stop us from trying to work out how the world works.

His demand for rigor did not, however, lead him to denounce metaphysics. He does not deny that a person can have a strong conviction about something and that they may apprehend some truth, only that such a conviction, because its validity cannot be tested by anyone who wishes to, is not science. Popper’s intention was not to overthrow metaphysics, only to properly demarcate genuinely empirical, testable questions from those that are not. Indeed, he noted, some things are not of a nature that can be verified or falsified.

Final Word

Late in the book, Popper compares the scientific project to the erection of a city on water: “Science does not rest upon solid bedrock. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles.”

Though it may only be a structure “built on piles,” and even if it never gives us the certainty we crave, science is still valuable; that Venice is not built on bedrock does not lessen the fact that it is nevertheless a worthwhile place to be. The same goes for philosophy.

Tomorrow…Jean-Paul Sartre and our freedom to invent a self.

Recommended book

The Logic of Scientific Discovery by Karl Popper

Share with friends