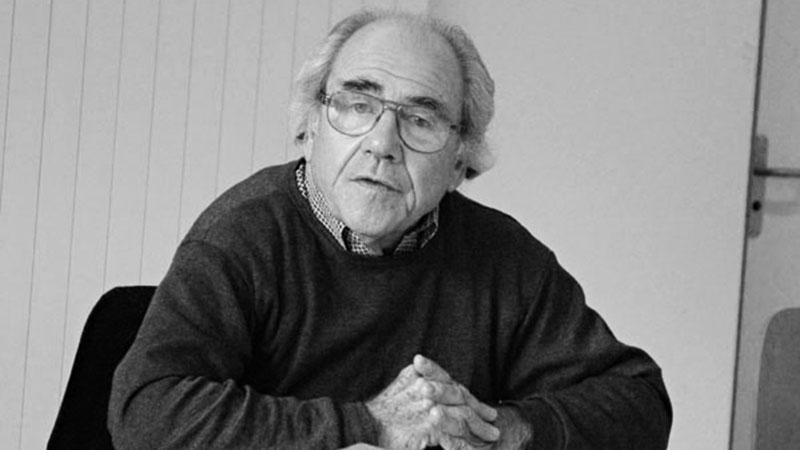

Jean Baudrillard

Episode #2 of the course Great modern philosophers by Tom Butler-Bowdon

In a nutshell: We no longer live in a world where signs and symbols point to truth; they are the truth.

Jean Baudrillard died in 2007, and we are still absorbing and processing many of his ideas. The greatest theorist of postmodernity, he was, strictly speaking, a sociologist, spending 20 years in the sociology department at Nanterre University in Paris. His career spanned the student revolts of 1968, the fall of communism, and the rise of what he calls the “hyperreal” order of media-centered capitalism.

Simulacra and Simulation was the book that made Baudrillard fashionable outside France, and it is surprisingly accessible. Though the examples he gives relate to culture and politics in the 1970s, for most readers, contemporary instances of his ideas will easily come to mind.

Baudrillard’s thinking marks a huge and rather subversive break from the traditions of Western philosophy, with its typical focus on questions of the self, free will, and knowledge and even the existentialist’s idea of living an “authentic” life. His vision is instead a world in which individuality is a myth and where people are units reflecting whatever is happening in the media, their only purpose to consume images and signs. In this new universe, something is real only if it can be reproduced endlessly, and what is singular or unshareable does not exist.

We no longer live in a world of the dual: being and appearance, the real and the concept. What is “real” can be endlessly produced from computer programs, and most disturbingly, this new reality no longer has reference to some rational base of truth:

“It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real…”

Baudrillard calls this new world the “hyperreal,” and one of its interesting qualities is that it obviates the need for the imaginary, since there is no distinction between reality and what is imagined. We are left with a world that is a “gigantic simulacrum” (a simulation or likeness), one that is “never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference.”

The Hyperreal Media Society

Presaging the rise of the internet and the social media phenomenon, Baudrillard notes that people are now measured by the extent of their involvement in the flow of media messages. “Whoever is underexposed to the media is desocialized or virtually asocial,” he says, and the flow of these messages is unquestioned as a good that increases meaning, just as the flow of capital is considered to increase welfare and happiness. One of the standout lines of the book: “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.”

Advertising is conventionally seen as superficial in relation to the actual things and products that it refers to, but in Baudrillard’s thinking, advertising is the core of our civilization. The commodities that it points to are relatively valueless—what matters is our identification with the stories, signs, and imagery that front those commodities; it is these that we desire and consume. We go shopping not so much to get things, but to keep ourselves within the boundaries of the hyperreal (to not want to consume these signs and symbols is subversive). The notion of a free-willed, rational individual is a total myth; we are best seen as entities fully wrapped up in, and part of, the technology and consumer culture.

Final Word

Philosophers have spent centuries arguing about the relative weight between “subject” (I) and “object” (the world), but Baudrillard saw the debate as having long since become insignificant—the object had won, hands down. A person today is not a project in selfhood, as many traditions of philosophy and theology have told us, but more like a machine that consumes and reproduces the ideas and images that are current in the media, advertising, and politics. And most disturbing of all, the replacement of reality with hyperreality, Baudrillard calls the “perfect crime” because most are barely aware that it ever happened.

Tomorrow…Simone de Beauvoir and “the Other” in philosophy.

Recommended book

Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard

Share with friends