Inception: Is Inception a Dream? (Is Your Whole Life a Dream?)

Episode #2 of the course Sci-Phi: Philosophy through science fiction by David Kyle Johnson, PhD

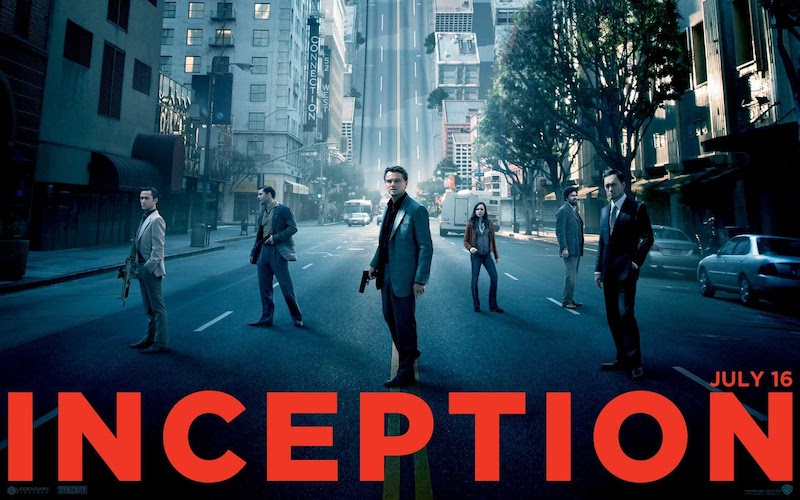

Christopher Nolan’s Inception is mind bending. Set in a world in which one person can enter the dreams of another, our protagonist, Dom Cobb, is hired by a wealthy businessman named Saito to perform an “inception”—to implant an idea in the son of a competing businessman named Fischer in such a way that Fischer will think he came up with the idea on his own. Saito assures Cobb that, if successful, he can arrange for Cobb to return to his estranged children.

Inception’s Questions

The movie follows Cobb’s “dream team” as they figure out a way to design a dream that will fool Fischer into thinking he should break up his father’s company. They’re successful, but the end of the movie is ambiguous. Cobb supposedly gets back to his kids, but after he spins his top (his “test” to tell whether he’s still dreaming), the film cuts to black before we see whether it falls.

But truth be told, many clues suggest the entire movie is a dream. Mombasa looks like one of Cobb’s “dream mazes” where walls literally close in around him. While Cobb is supposedly awake, many “dream cuts” occur (where we shift, mid conversation, from one locale to another). Cobb’s “dream forger,” Eames, is even able to conjure poker chips out of thin air—in the supposed real world. The film and the song Cobb uses to signal the end of a dream even have the same time stamp: “2:28.”

Descartes’ Inception

Centuries before the film, however, in what’s known as The Meditations, philosopher Rene Descartes realized that the same was true of our daily lives. In search of an unshakeable piece of knowledge on which he could base his scientific endeavors, Descartes searched through his own beliefs to find one that was undoubtable. An early candidate was that he was awake and experiencing the world; such a belief certainly feels certain, he thought.

But then Descartes recalled having vivid dreams that were accompanied by the same sense of certainty. So, he realized, even though he felt awake, he could still be dreaming. Indeed, for all he knew, the entire world might not even exist. All that might exist, Descartes realized, was him and a “malicious, powerful, cunning demon [that] has done all he can to deceive me” into thinking the world exists when it doesn’t. While he didn’t think this was true, Descartes concluded his inability to prove it false erased his ability to know that it was false—and thus made it impossible for him to know anything at all. This came to be known as “the skeptical problem.”

Descartes did finally find something he thought was undoubtable: the fact that he was doubting. You can’t doubt that you’re doubting, he said. In the very act, you prove it’s occurring. And if you’re doubting, you must exist. So, Descartes concluded: “This proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind.” It is from Descartes that we get the phrase, “I think, therefore I am.”

But Descartes’ attempt to prove the existence of the world from this lone bit of knowledge failed. Descartes thought he could reason from his own existence to God’s. The idea in my mind of God could only come from God himself, he thought. And if God exists, he wouldn’t allow me to be deceived into thinking the world exists when it doesn’t. But even if one may not be able to doubt without existing, it doesn’t follow that one couldn’t imagine God existing when he doesn’t or that God couldn’t have unfathomable reasons for deceiving us.

Solving the Problem

I personally think you can solve the skeptical problem by realizing that knowledge doesn’t require certainty. I can’t know for sure that I’m not dreaming—or being deceived by a demon or stuck in The Matrix with Neo—but that I am awake and experiencing the world seems to be the best (simplest, widest scoping, and conservative) explanation for my experiences. (Conversely, I think that the best interpretation of Inception is, “it’s all a dream.”) And that’s good enough for knowledge.

But speaking of The Matrix, the existence of the world is not the only thing that, at first, seems obvious but isn’t. That we have free will is simultaneously something that almost everyone believes is true, but that no one can seem to successfully defend. So, it’s to free will and The Matrix that I would like to turn to next.

Recommended book

Inception and Philosophy: Because It’s Never Just a Dream by David Kyle Johnson

Share with friends