Impressionism

Episode #1 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

Today’s lesson begins in the latter half of the 19th century in Paris, France, where a coterie of artists and intellectuals mingle at the Café Guerbois. Disillusioned by the Académie des Beaux-Arts’ taste for depictions of historically significant events and mythological subject matter, a new group of painters strive to capture the transience of the ever-changing world around them—a world that includes burgeoning industrialization and urbanization, the rise of the middle class, and the institution of democratic rule across former European monarchs. But unlike the Realists, who were more concerned with depicting the political and social milieus of their time, the Impressionists attempted to represent a visual “impression” of these fleeting moments, taking a completely different approach to capturing reality.

Édouard Manet. A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881–82. Oil on canvas. 37.5” x 51”. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, UK.

The anti-academic sentiment in France began with the accomplished painter Édouard Manet. His modern reinterpretation of Classical figures in his pieces Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863) and Olympia (1863) were considered too provocative for the public, anticipating his later preference for contemporary subject matter. His work also began to focus more on texture, tone, and color rather than traditional concepts of perspective or depth. Although Manet never identified with the core group of Impressionists, he was a huge inspiration for its key members, and his later works, such as A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1881-82), reflect a stylistic shift toward the impressionistic. For example, Manet uses a blurring technique, created through thick brush strokes and sharp saturated hues, to capture the motion of the swarming spectators and the dangling chandelier. He also “crops out” the man in the mirror in order to portray a “slice of life” as opposed to a staged or idealistic scene. These aspects speak both to the growing importance of texture, palette, and artistic manipulation in relaying meaning, as well as the increasing use of photography and its influence on understanding optics and perception.

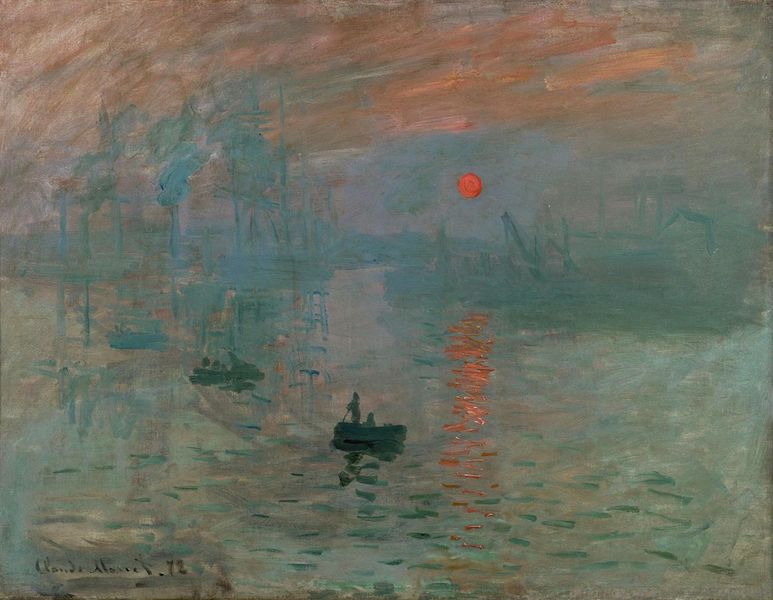

Claude Monet. Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas. 18.9” x 24.8”. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France.

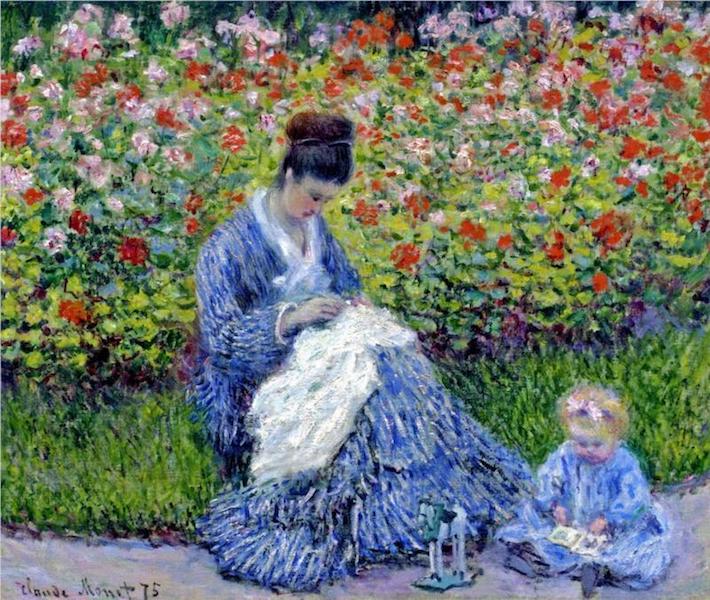

Claude Monet. Camille Monet et un enfant au jardin, 1875. Oil on canvas. 25.5” x 21.8”. Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, MA, US.

The Impressionists came to be known as such in 1874 during their first independent gallery showing—featuring works from artists such as Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot—when critic Louis Leroy dismissed Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) as a mere sketch or “impression.” Perhaps the most well-known member of the group, Monet’s attention to light, texture, and color encapsulates the approach of Impressionism. His use of “broken color,” as well as his choppy depiction of the sun’s reflection on the waves, speak to his desire to represent the transitory qualities of life. Rejecting the European modes of painting, Monet thus turned toward the asymmetry and vivid coloring of Japanese woodblocks, a phenomena known as japonisme that influenced several of the Impressionists. Monet’s painting environment was also unique. With the introduction of tubed paints, Monet would paint outdoors in a technique known as en plein air (translating to “in the open air”) instead of in the stillness and artificiality of the artist studio. This allowed him to capture ephemerality and movement more accurately, an aspect particularly notable in his Water Lilies series containing approximately 250 oil paintings.

Edgar Degas. Dance Class At The Opera, 1872. Oil on canvas. 12.6” x 18.1”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France, Paris.

Camille Pissarro. Landscape With Figures By A River, 1853-1854. Watercolor. 21.2” x 14.6”. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK.

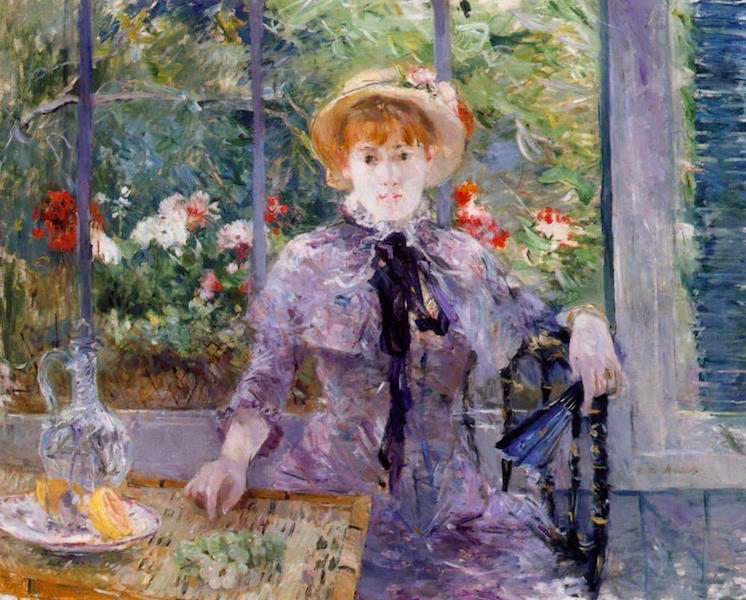

Berthe Morisot. After Luncheon, 1881. Oil on canvas. 31.8” x 39.4”. Private Collection.

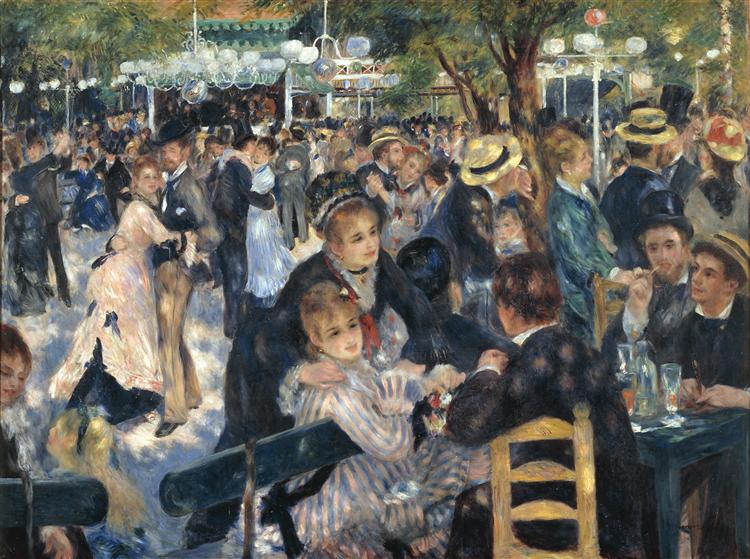

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876. Oil on canvas. 51.6” x 68.9”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Whereas Monet is best known for his representations of nature, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, another pioneer of Impressionism, is renowned for his interest in Parisian urban life and female sensuality. In his most appraised piece, Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876), Renoir portrays an effervescent kaleidoscope of bodies at the Butte Montmartre. The colors mingle and juxtapose under Renoir’s satiny brush stroke with as much energy as the clusters of people, utilizing photographic blurring and cropping techniques to further convey the animated vivacity of the courtyard.

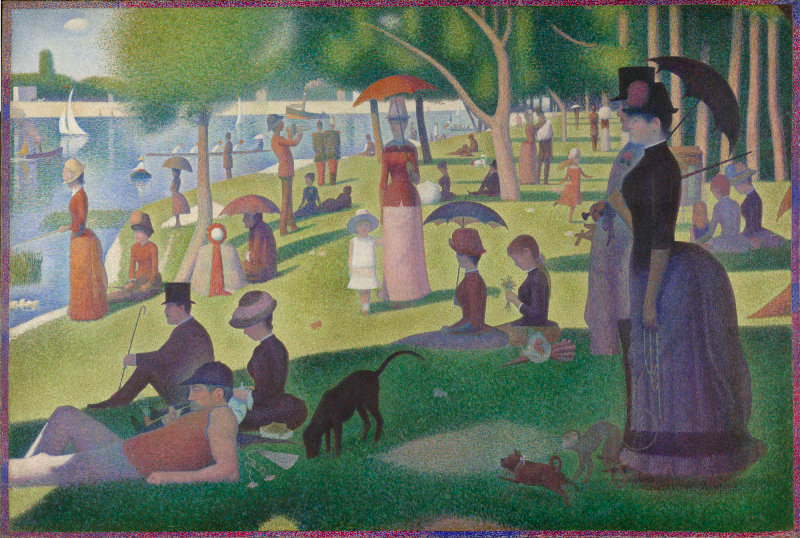

Georges Seurat. A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–86. Oil on canvas. 81.7” × 121.3”. Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

In 1886, the French Impressionists held their eighth and final exhibition. The artists were developing their own approaches and new techniques, such as Georges Seurat’s pointillism, hinting at the crumbling unity of the group’s style. Nevertheless, the Impressionists paved the way for future departures from traditional representations of subject matter and began an artistic inclination toward abstraction that would suffuse the art world in the upcoming decades—a shift that we’ll take a closer look at in the following days.

Share with friends