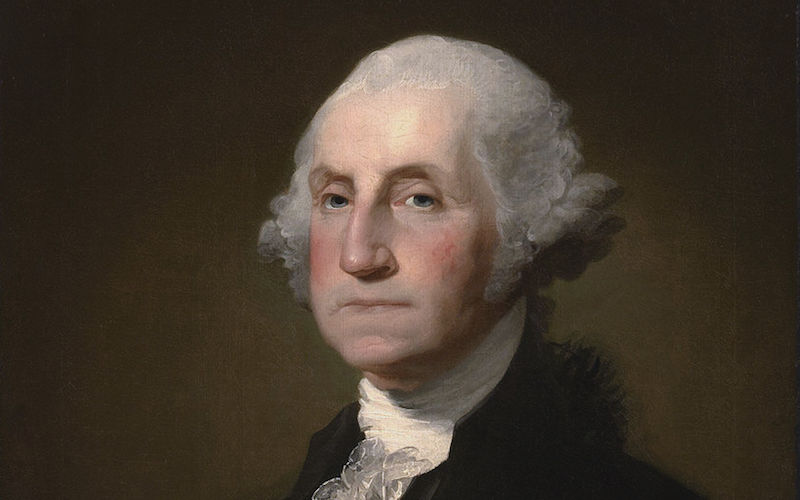

George Washington (1789-1797)

Episode #1 of the course Greatest US presidents by Patrick Allitt

Welcome to this course! My name is Patrick Allitt, and I’m a professor of American history at Emory University in Atlanta. Over the next ten days, I plan to teach you about ten of the strongest candidates to be considered the greatest presidents of the United States. The place to begin is with the first, and possibly the greatest, of them all: George Washington.

We know that the American republic survived its stormy early days, but in the 1780s and 1790s, no one knew whether it could last. George Washington, already a national hero for his leadership of the Continental Army, lent his prestige to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, when the fractious states were falling out with each other and when the Articles of Confederation were showing their frailty. Without Washington, the convention would probably not have been able to win assent for the constitution it drafted.

Next, he agreed to become the first president and was elected unanimously. Again, his unsullied reputation won over many Americans who feared the effects of too much concentrated power. Rather than be addressed as “Excellency,” “Majesty,” or “Highness,” Washington preferred the humbler title of “Mr. President,” and it has been used ever since. This title emphasized the difference between the United States as a republic and the monarchies of Europe.

Washington chose good advisors. Alexander Hamilton, his Secretary of the Treasury, was a particularly sensible choice. In a series of influential reports, Hamilton explained why the federal government should accept the debts of the different states, why the new nation should have a central bank, and why it should undertake a program of industrialization. All these policies were adopted, with favorable consequences.

The French Revolution broke out during his administration, soon followed by the Napoleonic Wars that shattered Europe. Some Americans favored supporting France in these wars; others favored supporting Britain. Washington remained aloof from both, arguing the advantages of neutrality. This principle, embodied in his farewell address (1796), became the basis of American foreign policy for the next hundred years. It enabled the United States to become a continental power and an industrial giant before being drawn into great power politics in the 20th century.

Ironically, it may be that the most important thing Washington did as president was to retire after two terms. He was eager to quit after one, but his advisors urged him to stay on. He could certainly have been president for life, or even king, but he recognized the importance of not letting himself, or any individual, become too powerful. He was proud of relinquishing command of the army at the end of the Revolutionary War, and he was equally proud of giving up the presidency after two terms. He modeled himself after Cincinnatus, the Roman hero who was called from the plow to rescue Rome in its hour of need, then returned to his farm rather than become a dictator. By establishing the two-term limit, which no successor challenged until 1940 and is now enshrined in a constitutional amendment, Washington ensured a regular rotation of chief executives.

Washington never lived in the White House, as it had not yet been built. As president, he lived first in New York, and then in the executive mansion on Market Street in Philadelphia. He approved plans for the building of a new “federal city” on a diamond-shaped area of 100 square miles astride the Potomac River, to be referred to as the District of Columbia. The federal city was later named in his honor. Congress first met there in 1800, and Washington’s successor, John Adams, moved into the new executive mansion the same year. When Washington resigned from the presidency, he returned to his plantation, Mount Vernon, just south of the district.

One final point: Washington, like many of the Founding Fathers, was a slave owner. Much to his credit, he was the only one of them to free his slaves, which he did at the time of his death in 1799. In countless ways, he was the ideal man to have been the republic’s first president.

In the next lecture, we’ll learn about another slave owner and president, Thomas Jefferson, who worked closely with Washington in creating and preserving the early republic.

Recommended book

Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow

Share with friends