Fauvism

Episode #4 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

Nuance, naturalism, subtlety, balance: these are terms that had come to hold much weight in the 19th-century French Académie Salons when discussing the belabored techniques of “desirable artwork.” While Monet’s swaths of Impressionist brushstrokes and Toulouse-Lautrec’s japonisme flattening had begun to challenge the well-wrought assumptions of what art is and can be, there was still a necessary abiding to realistic form and idealized beauty. Indeed, one can decipher the depth and perspective in Impression, Sunrise (1872) or the naturalistic hues and shapes in Jane Avril (1893). It was the Fauves (or “Wild Beasts”) that would be the first to carry the torch of these avant-garde movements into the 20th century. Invigorated with a similar disillusionment, the Fauvists catalyzed the shift toward abstraction later exemplified by the Cubists and brought the expressive possibilities of color to the forefront.

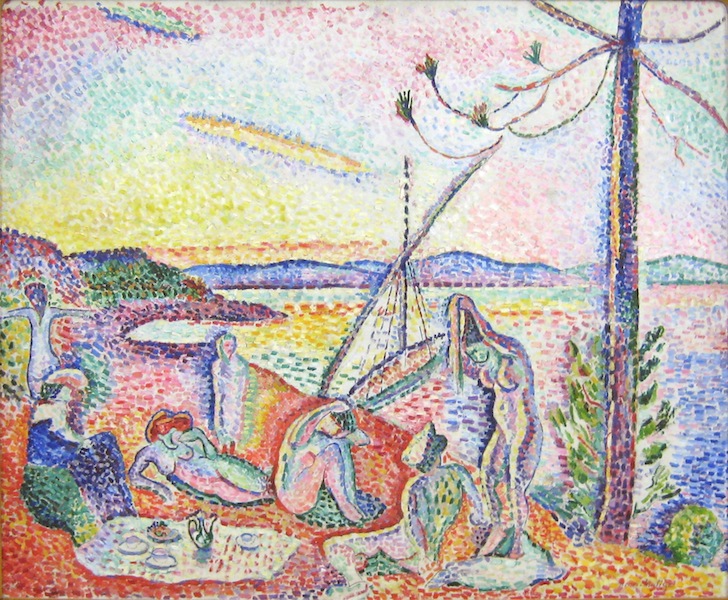

Henri Matisse. Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904. Oil on canvas. 38.8” x 46.65”. Museé d’Orsay, Paris.

Henri Matisse. Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904. Oil on canvas. 38.8” x 46.65”. Museé d’Orsay, Paris.

It was Henri Matisse’s initial experiments with Post- and Neo-Impressionist techniques that led him to the exploratory palettes apparent in Fauvism. For example, his proto-Fauvist piece Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904) utilizes Pointillist dotting and Divisionist coloration; however, unlike his predecessors like Seurat, Matisse’s colors create a brilliant, fantastical atmosphere featuring the full spectrum of pigments, evoking a sense of dynamism. Notably, the colors were not chosen for luminary or scientific purposes: as Matisse explains, “[i]t is based on observation, on feeling, on the very nature of each experience.”

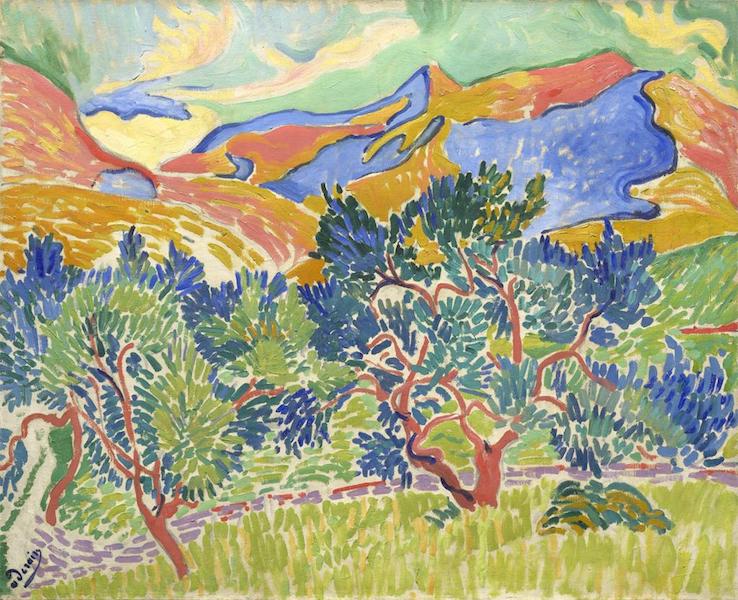

André Derain. Mountains at Collioure, 1905. Oil on canvas. 32” x 39.5”. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

In 1905, Matisse and a coterie of likeminded artists hosted the first Salon d’Automne in defiance of the traditional Salon. By this time, Fauvism had developed an idiosyncratic style, evident in Mountains at Collioure (1905). Derain maintains a purist approach to pigmentation, the colors brushed on the canvas in emphatic isolation. Moreover, he eschews realistic representation of his landscape; while the shrubbery is partly green, there are also complementary shades of blue, disorienting any naturalistic tendencies. Derain likens his “disharmonious” coloration to “sticks of dynamite,” the scene exploding off the canvas toward the viewer instead of providing depth. This is further emphasized through impasto, which involves daubing paint directly from tube to canvas and brushing it in short strokes, evoking motion and texture.

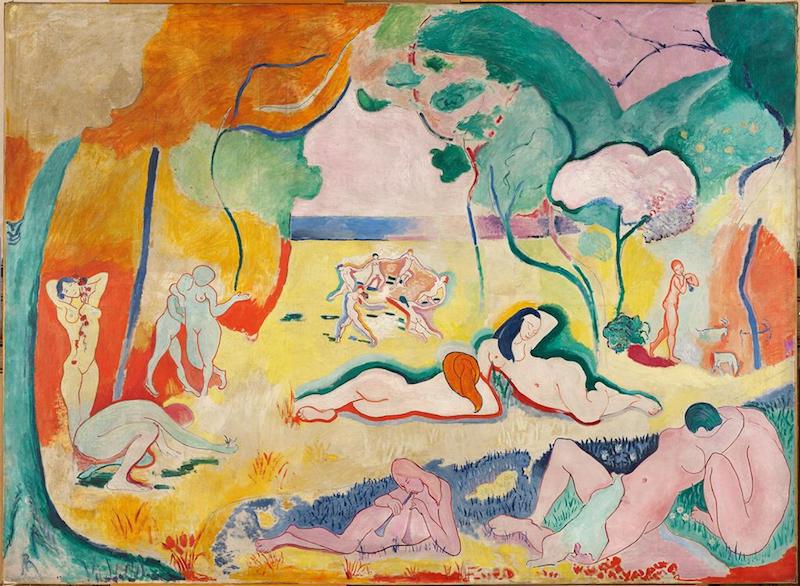

Henri Matisse. Le Bonheur de Vivre, 1905-06. Oil on canvas. 5’ 8.5” x 7’ 9.75”. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

The first Autumn Salon generally received negative reviews, so Matisse reacted with what would become the quintessential work of Fauvism: Le Bonheur de Vivre (1905-06). Matisse reconfigures the conventional pastoral and nude to embrace his innovations. The perspective has been completely flattened, and the bodies and trees are contoured with bold lines in folk-art fashion. Yet the expressive palette remains the most striking element. Critic Gelette Burgess would provide an acerbic description of this coloration during his 1910 review that would become America’s initial introduction to the Parisian avant-garde: “If you can imagine what a particularly sanguinary little girl of eight, half-crazed with gin, would do to a whitewashed wall, if left alone with a box of crayons, then you will come near to fancying what most of this work was like.” Nevertheless, the viewer cannot help but feel overwhelmed by the energy and passion evoked by the bodacious hues and soaring lines.

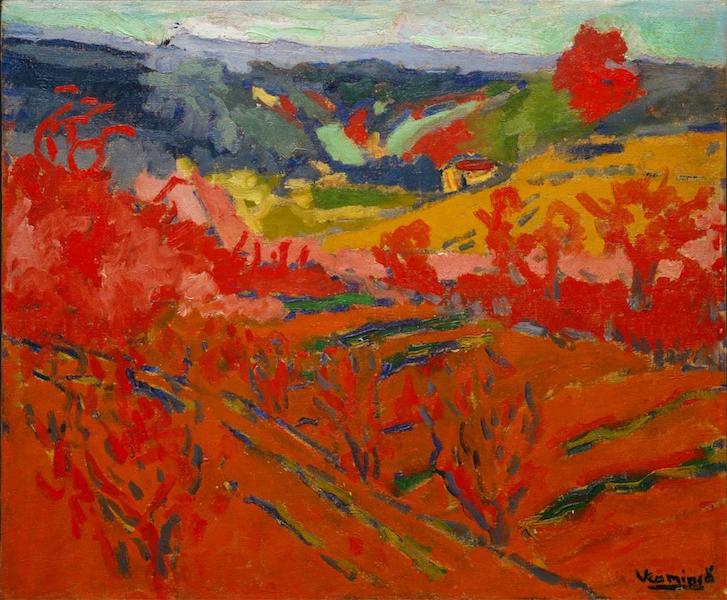

Maurice de Vlaminck. Autumn Landscape, c. 1905. 18.1” x 21.65”. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Color was thus the dominant mode of expression, even if it meant abstracting reality to unrecognizability. Maurice de Vlaminck’s Autumn Landscape (c. 1905) does just this with its blazing hues embodying the forefront. Vegetation is reduced to sporadic flames of red, contrasting with a chaotic sea of blues at the top of the canvas. For Vlaminck, Fauvism was more than expression—it was rebellion.

Though the Fauvists turned to other modes soon after, their ideas would live on through the Expressionists and Cubists, offering new standards for entering into an artwork. Tomorrow we’ll see just how these new standards altered the direction modern art would take in the upcoming years.

Learn Something New Every Day

Get smarter with 10-day courses delivered in easy-to-digest emails every morning. Join over 400,000 lifelong learners today!

Share with friends