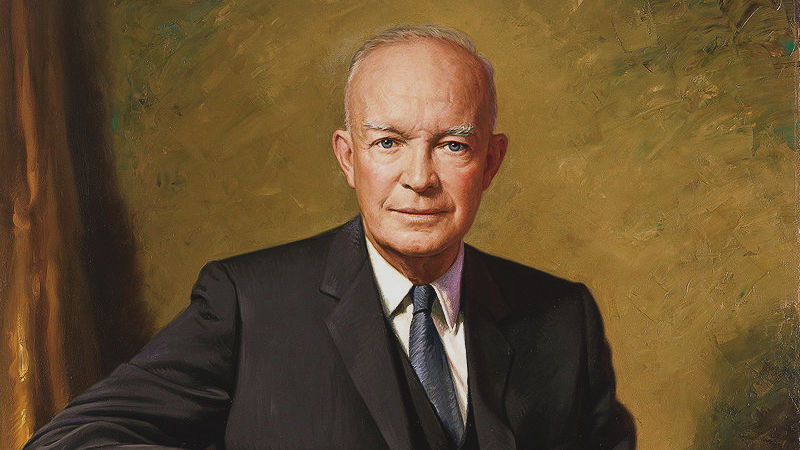

Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961)

Episode #8 of the course Greatest US presidents by Patrick Allitt

War heroes sometimes make excellent presidents: George Washington was a case in point. Sometimes they make bad presidents: Zachary Taylor and Ulysses Grant were fine warriors but poor national leaders. Dwight Eisenhower was so popular for his service in World War II as the mastermind of D-Day and the reconquest of Europe, both major parties asked him to be their candidate. He accepted the Republican offer in 1952 and defeated Adlai Stevenson that November. He is as memorable for what he did not do as well as for what he did do.

Many Republicans, whose party had been excluded from the top job since 1932, wanted him to roll back the New Deal and the giant federal bureaucracy it had created. Eisenhower refused. He recognized that an advanced industrial society must have an effective and powerful central government and at least a rudimentary welfare state. Otherwise, the terrible insecurities that citizens had felt in the early years of the Great Depression might return—and so might the disorders of an unregulated economy.

Eisenhower was less of an activist than Franklin Roosevelt and Truman, though he did undertake some major federal projects. One was the interstate highway system, inaugurated by legislation of 1956. As a young army officer after World War I, Eisenhower had been part of a truck convoy that tried to cross the United States by road and had averaged barely five miles an hour. He saw the defense benefits of having an efficient freeway system comparable to the German autobahns, which he had admired in the last months of the war.

A second initiative was the National Defense Education Act of 1958, passed after the Soviet Union’s success in launching Sputnik, the first orbiting spacecraft, in 1957. Eisenhower recognized the imperative need to educate first-rate scientists. He wanted to ensure the superiority of the American educational system over that of its cold-war rival, and was willing to use federal power to achieve it. He was less energetic when it came to desegregating America’s schools, even though his nominee to the Supreme Court, Earl Warren, had written the Brown decision in 1954 (the decision that declared that racial segregation was inherently unjust and unconstitutional).

Eisenhower’s best decisions came in foreign policy. Recognizing that America and the Soviet Union could now destroy one another with nuclear weapons, he worked to make sure it did not happen. That meant accepting the Cold War standoff, at least provisionally. Soon after inauguration, he ended hostilities in the Korean War, creating a truce that has held ever since. In 1956, he declined to intervene in Hungary in support of an anti-Soviet uprising, despite his sympathy for the rebels—it was just too dangerous.

Eisenhower also recognized that the days of colonial empires were coming to an end and that they should end. Although the United States was sending money and equipment to the French army in Vietnam as it struggled to suppress an anti-colonial uprising, he refused to send troops. France was humiliated at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and forced to quit. Even though he hoped an independent post-French South Vietnam might thrive, Eisenhower constantly rejected the option of sending American troops to support it. In view of what happened under his successors in the 1960s, this was a wise form of restraint.

Similarly, in 1956, when Britain, France, and Israel attacked Egypt in response to President Nasser’s seizure and nationalization of the Suez Canal, Eisenhower refused to support them. On the contrary, he put intense pressure on them to abandon the venture. It was, in his view, an unjustifiable form of imperialism, no longer supportable in a world where the democracies needed to court allies among the developing nations.

At first glance, it would be easy to underestimate Eisenhower’s achievement. Not acting is obviously less impressive than taking dramatic steps. But in a terrifying and volatile world, such as that of the 1950s, there’s a lot to be said for self-restraint and for accepting realistic limitations. By that measure, Eisenhower is one of the great presidents.

While Eisenhower stabilized the volatile Cold War in its early years, the first President Bush presided over its ending, calming what could also have been an explosively dangerous situation. We will meet him tomorrow.

Recommended book

Eisenhower in War and Peace by Jean Edward Smith

Share with friends