Dada

Episode #7 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

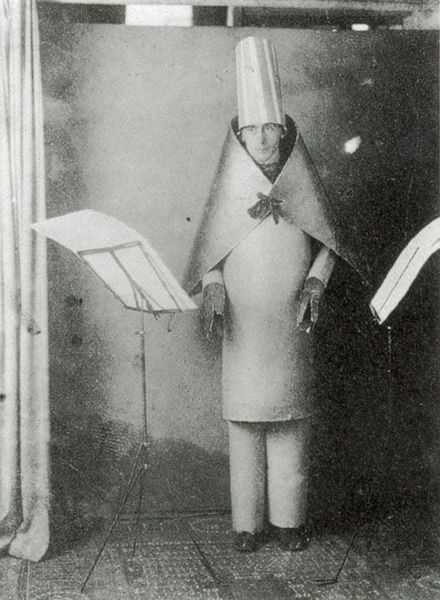

Today’s lesson takes us into the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, Switzerland during the calamitous year of 1916, when Europe was in the throes of World War I. Founded by Dadaist pioneers such as Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara, the nightclub was a space of artistic anarchy, political distress, and raucous, avant-garde performances. It was here Ball expressed his distaste for the nationalist and bourgeois mentality that legitimized violence, colonization, and class struggle through his sound poem “Karawane,” a nonsensical exploration of sound and emotion meant to echo the senselessness of WWI. The frenzied typography of the piece is just as unsettlingly experimental as Ball’s costume and performance, which included a cardboard cape and claws, giving him a mechanic appearance. But Dada was more than a mockery of current sociopolitical conflicts; it was an eschewing of convention, a ridicule of the rational, and a radical shift toward questioning not just the forms and functions of art, but the concept of art.

Hugo Ball reciting the Sound Poem “Karawane” at the Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, 1916.

Tristan Tzara. Unpretentious Proclamation, 1919.

The word “Dada” itself provides the theoretical underpinnings of its movement. As Hugo Ball states in his 1916 Dada Manifesto, “Dada comes from the dictionary. It is terribly simple. In French it means ‘hobby horse.’ In German it means ‘Good-bye,’ ‘Get off my back,’ ‘Be seeing you sometime.’ In Romanian: ‘Yes, indeed, you are right, that’s it. But of course, yes, definitely, right.’ And so forth.” Dada therefore defies the singular, logical understandings of traditional critique and objectivity; yet, as Tzara’s manifesto notes two years later, “Dada does not mean anything.” Tzara expanded on his theories in Unpretentious Proclamation (1919), a visualized manifesto in its own right. Appropriating typefaces from an array of sources, the piece replaces the aesthetically pleasing with erratic diction and crude typography, epitomizing the anti-art sentiment behind Dadaist works. As such, it can be viewed as the beginnings of conceptual art, utilizing materials, settings, and approaches to defy ideas rather than represent the world.

Marcel Duchamp. Fountain, 1917. Glazed ceramic and black paint. 15” x 19.3” x 24.6”. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA).

Therefore, in order to challenge the norms of capital-A Art, a new “aesthetic language” was necessary. One such method is evident in the early works of the Parisian expatriate Marcel Duchamp, who incorporated everyday or readymade objects into his work. His most provocative piece, Fountain (1917), features an upside-down urinal with the signature “R. Mutt”. A play on the elegant Renaissance depictions of similar subject matter, it is a shocking yet amusing rejection of traditional artistic technique. However, it is the title that truly makes this a readymade, for Duchamp controversially disturbs the connotations of “urinal” and “fountain.” This irreverent attitude toward art and society was a notable feature of Dadaism, exemplified through satire, irony, wit, and parody.

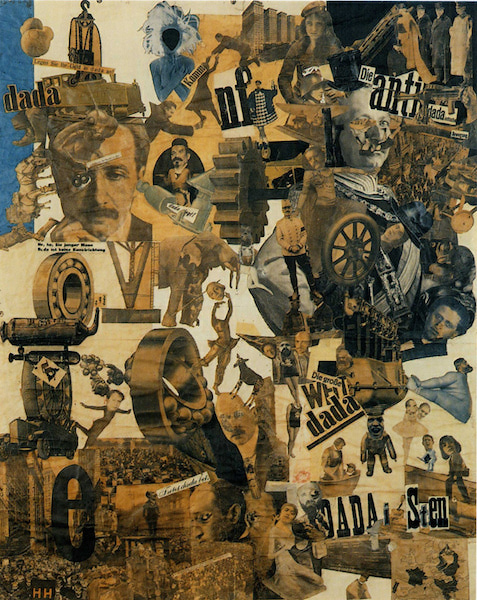

Hannah Höch. Cut with a Kitchen Knife: Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1919. Photomontage and collage with watercolor. 44.9” x 35.4”. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany.

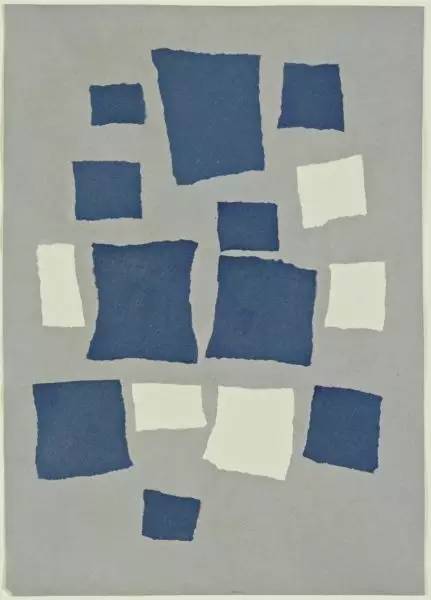

Jean (Hans) Arp. Untitled (Collage with Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance), 1916-17. Torn-and-pasted paper and colored paper on colored paper. 19.1” x 13.6”. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

To further subvert the authority of the “artist,” Dadaists also embraced photomontage, collage, and assemblage. In her most renowned piece Cut With a Kitchen Knife (1919), Berlin artist Hannah Höch presents a chaotic montage of political, cultural, and textual cut-outs representing “anti-Dada” and “Dada” figures and objects. Höch not only juxtaposes the radical with the conservative as a way of critiquing German culture, but also reconfigures feminine identity by including several female figures and even her own self-portrait. In this exploitation of modernity, Höch effectively blurs the lines between the domestic and social spheres, as well as between hobby and serious art.

Other Dadaists, like Hans Arp, included acts of chance in their work. In his Untitled (Collage with Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance) (1916-17), Arp relinquished all agency by sporadically ripping and dropping colored paper onto larger sheets, thus challenging the modes of production in making art and questioning the competence of logic and reason.

Even though many Dadaists would turn toward Surrealism, social realism, and other artistic modes in the 1920s, the impact of Dada resonated through the 20th century in action painting, zine culture, and beyond.

Share with friends