Cubism

Episode #5 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

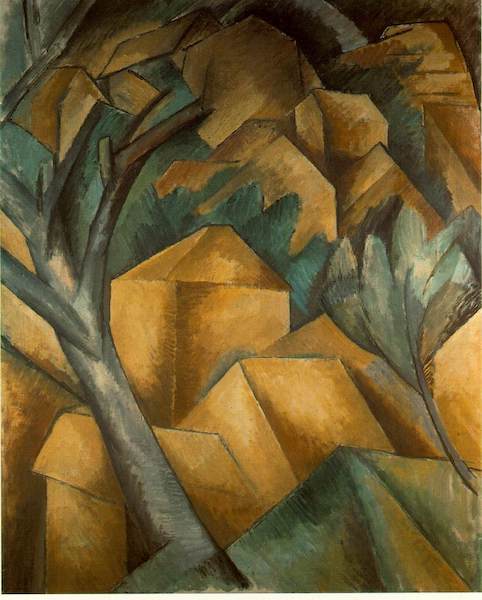

We begin today’s lesson by placing ourselves in the shoes of critic Louis Vauxcelles as he contemplates the abstracted landscape painted by Georges Braque. Compared to the colorful, impasto night sky of van Gogh or the blurred, broadly brushed ponds of Monet, Braque’s landscape is jarringly nonrepresentational. The buildings are simplified into near-uniform boxes; the trees have lost their organic texture, replaced by rectangles and triangles, and the linear perspective is disrupted through a collage-like layering effect. These disorienting qualities would lead Vauxcelles to claim in the Parisian periodical Gil Blas that Braque “despises form, reducing everything, places and figures and houses, to geometric schemas, to cubes.” It was through this observation that Cubism received its name and its eventual status as one of the most influential (albeit controversial) art movements of the 20th century.

Georges Braque. Houses at l’Estaque, 1908. Oil on canvas. 15.9” x 12.7”. Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France.

Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907. Oil on canvas. 8′ x 7′ 8″. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Braque’s painting was largely informed by the experimental tendencies of fellow painter Pablo Picasso, particularly his piece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). In this painting, Picasso realizes the potential of the canvas, rendering five women—or, as some critics argue, one woman from multiple perspectives—two-dimensionally, thus embodying more than one time-space and refuting illusionism. With its harsh lines and disordered palette, Picasso asks the viewer to engage with art beyond representation, a revolutionary concept during a time of colonial might, burgeoning industry, and the belief in Western dominance. As such, Picasso turned toward what was described as primitive art at the time, evident in the African-influenced masks of the women, who gaze back at the viewer. Whether these representations of colonial “others” or gendered bodies is exploitative or empowering continues to be highly contested.

Pablo Picasso. Ma Jolie, 1911-12. Oil on canvas. 39.4” x 25.2”. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Picasso and Braque worked closely during the 1910s and would develop two key movements within Cubism. The first period between 1908-1912, known as Analytical Cubism, fractured and reimagined the form, structure, and line of an artwork—aspects that were largely neglected by the varicolored works of the Impressionists and Fauvists. The hermetic abstraction, geometric shapes, and right angles, as well as the monochromatic hues and multiple, contradictory planes, are meant to depict simultaneous perspectives and compacted energy. In Ma Jolie (1911-12), Picasso flattens the picture plane even further by inserting the words “Ma Jolie” across the bottom, as well as other written elements such as a treble clef, pushing the limits of dimension.

Juan Gris. The Sunblind, 1914. Gouache, paper, chalk and charcoal on canvas. 36.2” x 28.3”. Tate Modern, London.

In the latter months of 1912, the Cubists wished to eradicate depth even further and began incorporating aspects of everyday life through papiers collés. This time frame between 1912-14 became known as Synthetic Cubism, eloquently described by Juan Gris when reflecting on his own approach: “My art is an art of synthesis … I consider that the architectural side of painting is mathematical, the abstract side, I want to humanize it.” As made apparent in Gris’ still life collage The Sunblind (1914), color is reintroduced as a vital aspect of this synthetic process, but the main focus remains on structural composition: angular forms and diagonals clash, while the chalky blues contrast texturally with the newspaper headline. Though Gris meshes real life objects with artistic placement, the reality evoked by The Sunblind is hardly representational; rather, it recognizes the world as a place of scattered referentiality, simultaneity, and paradox.

Though Picasso and Braque are largely considered the founders of Cubism, recent scholarship has begun to look at the “Salon Cubists,” or those artists such as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger who exhibited their works more publicly, as offering a distinct voice and expanding Cubism’s reach beyond the avant-garde. Nevertheless, Cubism’s impact on aesthetics, approach, and form was astronomical, redefining the possibilities of artistic medium and showcasing the innovative and subversive power of anachronism, perspective, and abstraction.

Share with friends