Art Nouveau

Episode #3 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

The late 19th century was an age of industrial revolution and technological innovation paralleled by the emergence of historicism in architecture and visual art. Design turned toward Victorian superfluity, methods of mass manufacturing, and the ennoblement of Western values, and several artists reacted against these conceptualizations of art. On one hand, Post-Impressionism introduced a provocative use of color and line, and Aestheticism called for non-narrative and symbolic works of “art for art’s sake.” On the other hand, the Arts and Crafts Movement encouraged traditional modes of production such as handcraftsmanship. Yet, it was Art Nouveau, manifesting rapidly across Europe in the 1890s, that incorporated all of these aspects, striving for gesamtkunstwerk (or “total work of art”) by incorporating multiple media, derailing historic stylization, and eliminating the hierarchy between liberal and decorative arts.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Jane Avril, 1893. Lithograph. 48.8” x 35.0”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

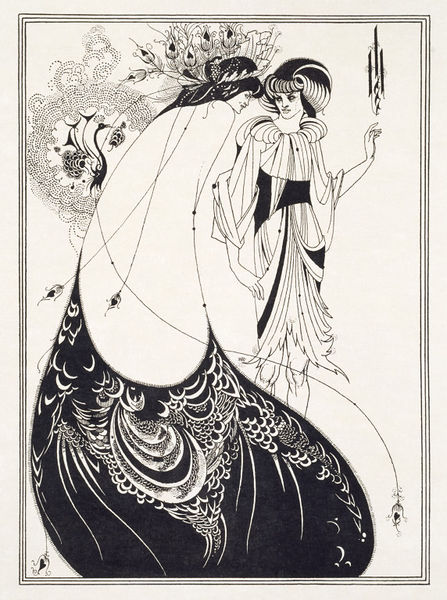

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley. The Peacock Skirt, 1894. Line block print on Japanese vellum. 8.9” x 6.3”. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The rise of experimentation in asymmetrical design and fluid linework can be traced to graphic artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Aubrey Vincent Beardsley. While Toulouse-Lautrec’s Jane Avril (1893) depicts the eponymous can-can dancer with energetic color and simple, rhythmic contours, Beardsley’s The Peacock Skirt (1894) alludes to Oscar Wilde’s iconic Aestheticist play Salomé (1892), evoking decadence through thin, curvaceous lines against bold negative space. Most notably, both artists flatten their subject matter in the style of japonisme, mimicking the Japanese woodcuts that became popularized in the West in the 1890s. Due to the ubiquity and accessibility of periodicals, posters, and other print media, these pieces helped expose Art Nouveau tendencies to a larger audience and brought printmaking techniques to a new level of artistry.

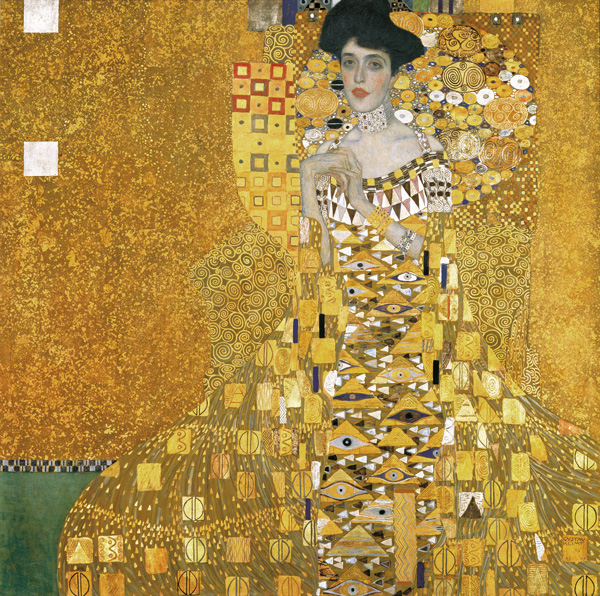

Gustav Klimt. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907. Oil, gold and silver leaf on canvas. 54.3” x 54.3”. Neue Galerie, New York.

Of the visual artists working at this time, Viennese painter Gustav Klimt is perhaps the most recognized trailblazer of Art Nouveau—or, as it was called in the Austro-Hungarian and German empires, Jugendstil. His first portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer exemplifies the movement’s fusion of ornamentation and representation. The brilliant sheen over the gold and silver leaf dominates the picture plane, exuding a decorous, bountiful beauty that is juxtaposed with Bloch-Bauer’s blank stare and exposed shoulders. Overall, its titillating use of abstraction and irregular patterning indicates Klimt’s desire to create an art that was, quite literally, new.

Victor Horta. Museum and House of Victor Horta, 1898-1901. Brussels, Belgium.

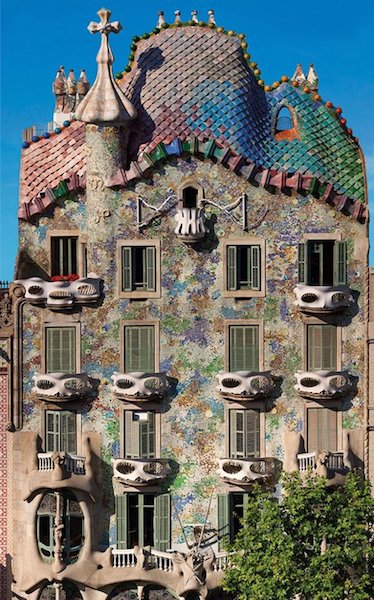

Antoni Gaudí. Casa Batlló, 1904-07. Barcelona, Spain.

The gesamtkunstwerk effect of Art Nouveau was realized on a large scale through the sinuous, organic designs of architects such as Victor Horta and Antoni Gaudí. Though these buildings are quite distinct from each other, they utilize similar approaches that are inspired by the biomorphic structures of nature. Victor Horta’s home-turned-museum incorporates vine-like ironwork and varying widths along the facade to capture the fluid, multileveled interior. By contrast, Gaudí utilizes a trencadís mosaic technique and floral patterning to create a fantastical and animated Modernisme castle that recalls the legend of St. George and the dragon he slayed.

Louis Comfort Tiffany. Water Lily Table Lamp, 1904-15. Leaded favrile glass and bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Louis Sullivan. Carson, Pirie, Scott Building [entrance exterior], 1899-1904. Chicago, Illinois.

This European art movement would eventually make its way overseas and influence the designs of American artists as well. Louis Comfort Tiffany, influenced by the glasswork showcased at the Paris Exhibition of 1889, invented an iridescent, favrile glass that would become a trademark of Art Nouveau, particularly its ever-changing coloration and flowery qualities. Meanwhile, Louis Sullivan added expressive, ornate eccentricities to his largely Modernist structures of “function over form.” The entrance to Carson, Pirie, Scott Building (1899-1904) is especially striking in its finite linework accented with Gothic intricacies.

Despite its international scope, the embellishment and elegance of Art Nouveau was soon overcome by Modernist design, which looked toward the medium or form itself to create its meaning and structure. Nevertheless, the movement was a crucial precursor to the experimentations in abstraction, palette, and configuration that would dominate the first half of the 20th century. Check in tomorrow as we continue our venture through the art of Modernity.

Share with friends