Abstract Expressionism

Episode #8 of the course Art movements of Modern Art by Cameron MacDonald

Until World War II, the cornucopia of contemporary art was Europe, where a myriad of aesthetic “-isms” had emerged in reaction to representational, traditional techniques. From Cubism to Expressionism, Surrealism to Futurism, the Modernist artistic movements of the 1910s to 1930s were not so much a singular step away from the Old Masters as they were a frantic explosion of new and profound applications with bold, idealistic stances and manifestos. From across the Atlantic, a small coterie of emerging American artists (later known as The New York School) were studying these movements, both in dismay and awe.

Arshile Gorky. Garden in Sochi, 1943. Oil on canvas, 31” x 39”. Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

Arshile Gorky. The Liver Is The Cock’s Comb, 1944. Oil on canvas, 73 ¼” x 98”. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, USA.

The term “abstract expressionism” was first coined by art historian Alfred Barr Jr. in 1929 when describing the work of Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky’s nonfigurative style, as well as the surrealist works of André Breton and Max Ernst, were all major influences on Armenian-American painter Arshile Gorky, considered to be a key figure in the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. Gorky’s artistic innovations, such as his attention to natural, biomorphic shapes and the texture of the medium itself, are exemplified in his work Garden in Sochi. What differentiates Gorky’s work from that of the surrealists and expressionists before him is his ability to disregard representation completely, replaced with an intense and romantic dynamicism based on improvisatory technique. There was no manifesto for the work that Gorky was pursuing, and this would inspire a plethora of artists disillusioned by the institutionalization of expressive and creative freedom.

Jackson Pollock. White Light, 1954. Oil, enamel, and aluminum paint on canvas, 48 ¼” x 38 ¼”. Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA (Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection).

Jackson Pollock. Autumn Rhythm, 1950. Enamel on canvas, 105” x 207”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

Perhaps it is the New York School poet and art critic Frank O’Hara who describes the movement best: “You just go on your nerve.” There were several techniques that emerged meant to capture the spontaneity and liberation that art could provide in a time of political and ideological collapse. For example, Jackson Pollock developed the widely recognized drip technique or action painting, in which the whole body was utilized to splatter, splash, or fling paint across large canvases. The aim of Pollock’s technique is highlighted in art critic Harold Rosenberg’s prolific essay “The American Action Painters” (1952), which states that “what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” Overall, Pollock’s revolutionary painting style brought vitality, energy, and life back into painting.

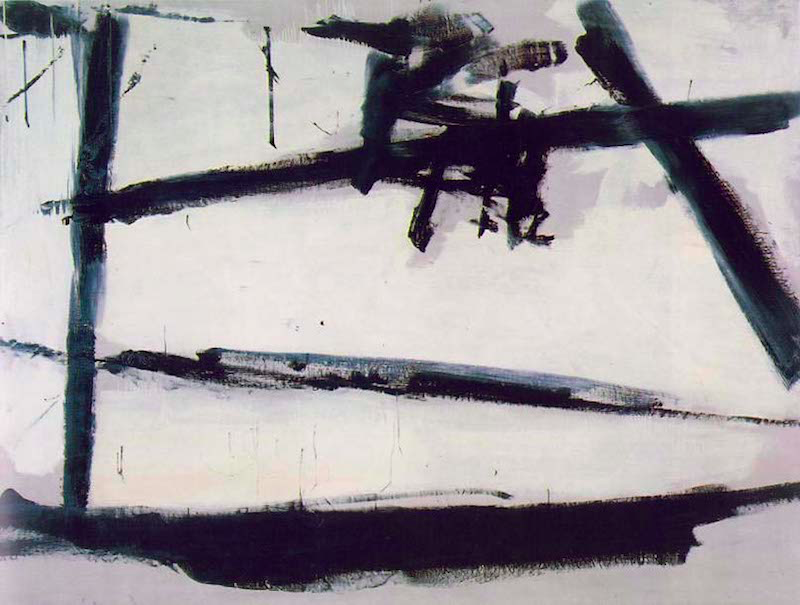

Franz Kline. Painting Number 2, 1954. Oil on canvas, 6’ 8 1/2″ x 8’ 11″. Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

Mark Rothko. No. 3/No. 13 (Magenta, Black, Green on Orange), 1949. Oil on canvas, 85 3/8″ × 65″. Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

As such, it was the very act of painting that was highlighted above the subject matter. From the violent palettes and brushstrokes of Willem de Kooning to the soft yet penetrating use of color in a Mark Rothko piece (whose work would coincide and anticipate the Color Field and Minimalism movements), the Abstract Expressionists put America on the art world map by the late 1940s to early 1950s. Along with Pollock, de Kooning, and Rothko, as well figures such as Hans Hoffman and Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline made a considerable impact on this rising form of artistic expression, particularly through his abstraction and awareness of the painterly surface. In Painting Number 2, Kline’s thick slashes of black across a white canvas would become his signature. Both architectural and calligraphic, splotchy and bold, Kline captures some of Pollock’s visceral technique while channeling the minimalism of Barnett Newman.

By the end of the 1950s, the gestural and corporeal vitality of the Abstract Expressionists began to wane. The movement was critiqued for its impervious abstraction and contradictory “antimodern” motives, thus making way for a return to the material and objective through Pop Art.

Share with friends