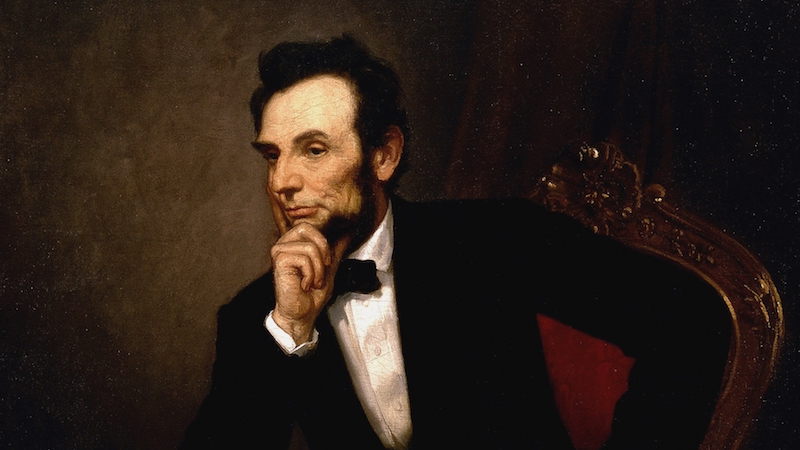

Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865)

Episode #3 of the course Greatest US presidents by Patrick Allitt

It would be hard to leave Lincoln off the list of great presidents, even if the list consisted of only two names—or just one. President during the Civil War, he dedicated himself to preserving the Union, doing everything necessary to achieve his end, including the abolition of slavery.

Born in frontier Kentucky and raised in frontier Illinois, he was a talented lawyer, briefly a soldier, and a rising politician in the new Republican Party of the 1850s. His debates with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas in 1858 gave him a nationwide reputation and led to his presidential nomination in 1860. Eleven southern states responded to his election victory by seceding from the Union. Lincoln and the Republicans denied their constitutional right to do so, declared them to be in rebellion, and went to war to bring them back.

Among his hardest tasks was finding adequate generals to lead Union armies. Some were poor organizers, some shied away from battlefield confrontation, and some were political schemers against his authority. In 1864, however, he promoted Ulysses S. Grant to command all the Union armies, after Grant’s successes at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga in the West. He stuck with Grant in the face of blistering criticism, despite the casualties Grant incurred in battles of grinding attrition around Richmond. Grant repaid him with victory.

One of Lincoln’s challenges was keeping the loyalty of slave states that had not seceded, including Maryland, Delaware, and Kentucky. When he issued the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year’s Day of 1863, it applied only to slaves in the Confederate states. Lincoln had not been an abolitionist before the war; he issued the proclamation not for idealistic reasons but because of its military usefulness. For the same reason, he ordered that former slaves could fight in the Union army and if taken prisoner, should be treated with the same respect as white Union prisoners. Despite his motivation, the effect of these decisions was profound and permanent.

Lincoln had to balance citizens’ rights against military necessity. In 1861, he ordered the arrest and detention, without trial, of prominent “Copperheads,” northerners who were obstructing the war effort, and he ignored a court order to desist. He persuaded Congress to pass an act enabling him to suspend habeas corpus (the right to due process) in the case of suspected spies and saboteurs and imposed martial law in war-torn areas.

On the other hand, he permitted hostile newspapers to criticize his administration until they began running deliberately false stories in 1864, threatening the conduct of the war. Most historians have been more impressed by Lincoln’s restraint than by his forcefulness in this area. He did not try to hinder the election of 1864 even when it looked as though he might be defeated by disgruntled ex-general George McClellan, a Democrat. In any event, he won a second term.

For his speeches alone, Lincoln deserves a central place in American history. His two-minute Gettysburg Address was a miniature masterpiece; it transformed the battlefield into a sacred site in the history of democratic self-government. His second inaugural address made national atonement for slavery. But as he put it, “with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right,” he also held out an olive branch to his almost defeated enemy.

Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 turned a successful politician into a martyr less than a week after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox. Northern whites compared him to Jesus Christ, who had died a sacrificial death to save sinners. Former slaves compared him to Moses, who had led his people out of Egyptian slavery and into the Promised Land. The symbolic dimensions of the Lincoln legend are unmistakable. But they should not prevent us from recognizing that he was also a masterful Washington operator, excelling in the nuts-and-bolts work of everyday politics.

Tomorrow, we’ll meet Theodore Roosevelt, who was only six when Lincoln was killed and who regretted having missed the chance to fight for the Union.

Recommended book

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald

Share with friends