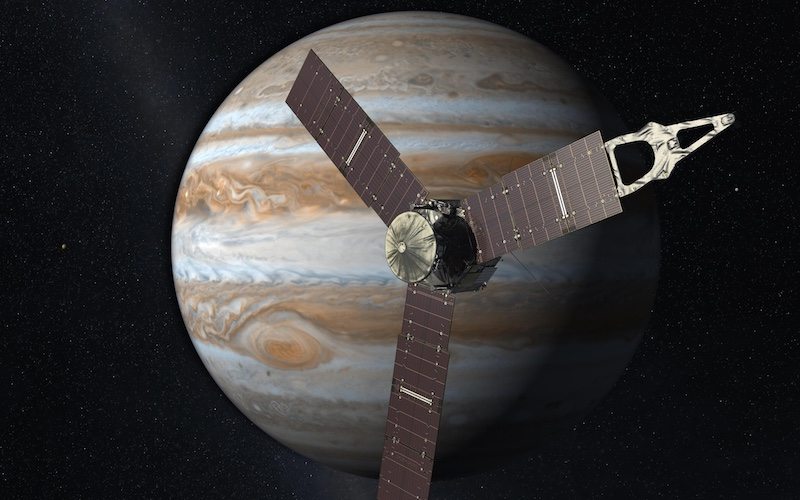

Juno, the Jupiter Orbiter

Episode #5 of the course “Most ambitious science projects”

Prior to Juno reaching Jupiter’s orbit in 2016, the spacecraft, guided by the gas giant’s forceful gravity, accelerated to more than 134,000 miles (~215,652 km) an hour, making it one of the speediest human-built machines ever constructed.

Juno spans 66 feet (~20 m) in diameter and is 15 feet (~4.6 m) tall. Once in rotation, the machine will complete 12 science orbits around the planet and then crash directly into it in June 2018. On its death mission, the craft will plow into Jupiter’s hydrogen atmosphere until it burns up, similar to a meteor. Juno cost nearly one billion dollars to build and costs 30 million dollars a year to maintain. There are hundreds of personnel charged with keeping Juno running.

Uses for Science

As Juno rounds Jupiter, a package of nine tools examines the planet’s several layers. Since Jupiter is so huge, it has kept its level of gravity and some of the old elements of the early solar system, primarily hydrogen and helium. This component of Jupiter sets the planet up as a valued portal into learning about the beginning of the solar system. Gauges of Jupiter’s magnetic field may ultimately stop the argument about whether the nebulous has a rocky center.

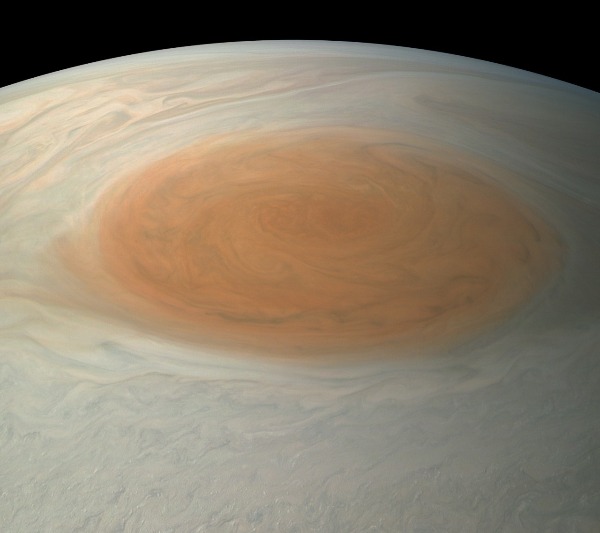

Jupiter’s clouds captured by Juno spacecraft

Juno’s magnetometers can demonstrate the movement and depth of the metallic hydrogen ocean found in the inner parts of the planet, which produces the biggest magnetic field in our solar system besides the one found around the sun. Lastly, a microwave radiometer will find out the measure of water on Jupiter’s surface, which is critical to assessing how Jupiter was first formed.

The Great Red Spot captured by Juno spacecraft. Juno data indicates that the iconic storm is almost one-and-a-half Earths wide, and has roots that penetrate about 200 miles (300 kilometers) into the planet’s atmosphere.

Uses for Practical Life

Examination of Jupiter’s intricate weather history would assist meteorologists in predicting Earth’s weather patterns, but for right now, this remains in the realm of scientific research.

Share with friends